New approaches to international development – seen through a creative lens

Cartoons, films and music are being used to interpret key themes raised in an academic analysis of international development. This unorthodox and experimental approach brings fresh perspectives and engages new people, the British Council has discovered.

When Professor JP Singh heard the British Council’s plan, he wasn’t entirely convinced. “I didn’t know what to expect,” says the professor of international commerce and policy at George Mason University in the US. The British Council had commissioned 12 artists to illustrate his paper that outlined a theoretical framework for cultural relations approaches to international development. “Although it’s about art, and I work in that area,” says Singh, “I’ve just never had artists interpret a very academic paper.”

Kazz Morohashi was similarly hesitant when faced with the project. “It was a little difficult to get my head around it. Initially, I had to read it a couple of times,” says the artist who is finishing her PhD in museum learning design at the Norwich University of the Arts. But after a period of nine months working with JP Singh and the other artists, the Japanese-born, UK-based creative produced a work which somehow manages to distil some of the ethics and practices of new approaches to development work into a two-and-a-half-minute animated video about a toy rabbit and his floristry business.

“DICE was born of a British Council initiative to try to bring together our work in the arts and civil society,” says Adam Pillsbury, a global stakeholder manager at the organisation. Launched in 2018, Developing Inclusive and Creative Economies (DICE) was a three-year pilot programme designed to foster cultural and economic agency. A key strand of the programme was a £2m fund to support creative and social enterprise. It targeted women and girls, youth, people with disabilities as well as other marginalised groups in the six target countries of Brazil, Pakistan, South Africa, Egypt, UK and Indonesia.

- Read more about DICE: New support for creative and social enterprises in the UK and overseas

“From its very inception, DICE championed the role of artist in both addressing social challenges but also in conveying the programme’s themes, ethos and aims through artistic media,” says Pillsbury. “So when we received Professor Singh’s rich, complex academic paper on the DICE programme and cultural relations approaches to international development, it was an ideal opportunity to put these beliefs into practice.”

From comic strips to song

After a callout, artists from each of the target countries were selected to highlight key themes of the text, The Cultural Relations of Negotiating Development: Developing Inclusive and Creative Economies at the British Council, and re-interpret them. The results were strikingly varied, ranging from comic strips to an actual song. This unorthodox and experimental approach is at the heart of the DICE programme and brings to life ways of working explored in Singh’s text. Singh calls these different artistic approaches to the paper and programme “refreshing”.

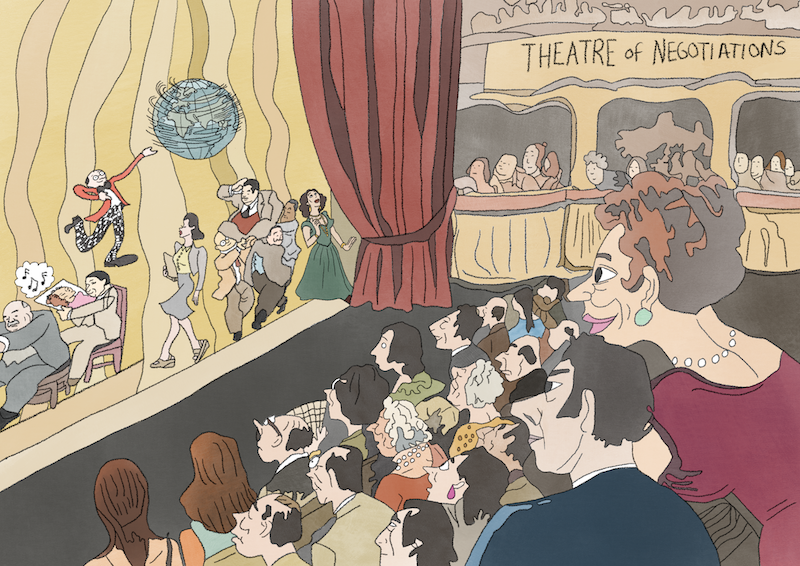

Egyptian artist Nadine Nour El Din produced a series of satirical drawings. One of them, The Theatre of Negotiations, illustrates the performative aspect of development work and what Singh calls its “habits of argumentation, negotiation and deliberation”. Her second drawing explores what Singh refers to in his paper as “the elephant in the room”; that is to say the issue of colonialism and power imbalances in development work. The artist did not want to visualise the metaphor too literally as she associated the animal with India rather than Egypt. She instead portrayed her country as a young girl lectured by an old man in a suit.

Morohashi’s work is just as playful but takes a different tack. She decided to sidestep issues of race and class in favour of a more universal approach. She drew on the Japanese tradition of anthropomorphology: “Japan has this very strange, relaxed attitude about blending the natural kind of the animal world, and the human world.” In the video, the rabbit gains confidence in its talent as a florist through the support of others. This was meant to illustrate DICE’s aim of forging connections between different stakeholders. “I took away the idea of ‘co-crafting’ as a method of developing a community of practitioners, where committed individuals come together to master their own craft within a long-lasting ecosystem of creative support,” she says.

At the forefront of thinking

This way of working is what puts the DICE programme at the forefront of thinking in development and both effective and cost-effective methods of engaging people. “In those instances, art and artists stand up really well,” says Stephen Stenning, head of art and society at the British Council. The DICE project brought together a collection of different actors, from artists and musicians to young people and marginalised communities. Many of them hadn’t been involved in development work before.

It is about finding ways of doing things in context, a way of working with people that is not designed for people or imposed upon people but grows out of a collective endeavour

Singh is glad for anything which might make the theories that underpin projects like DICE more accessible. “DICE is making contributions that need to be understood,” says Singh. For decades many development projects have followed a top-down approach, mainly informed by Keynesian economics. “There would be these huge projects conceived in the World Bank or IMF and rolled out anywhere in the world and we thought we had a magic formula to do it,” says Singh.

That formula, however, didn’t involve helping development partners express what they wanted out of the relationship. “I think it is about finding ways of doing things in context, a way of working with people that is not designed for people or imposed upon people but grows out of a collective endeavour.” says Stenning. “I think arts and creativity is absolutely essential to that.”

Header image: Egyptian artist Nadine Nour El Din's illustration explores “the elephant in the room”– the issue of colonialism and power imbalances in development work. She portrays her country as a young girl lectured by an old man in a suit.

There is a booklet and catalogue featuring all the works of art and the quotes that inspired them, a video and Professor Singh’s paper on the British Council’s DICE Artist Commission page.

An exhibition is being held at the Van Metre Hall Art Gallery in the Mason Square campus of George Mason University in the USA until 13 May 2022.