BRUTUS: Ski jackets for tsunami orphans? Go figure.

In the first instalment of our new Brutus column, Arthur Wood reports on a new piece of work on 'Resiliency' for the Rockefeller Foundation.

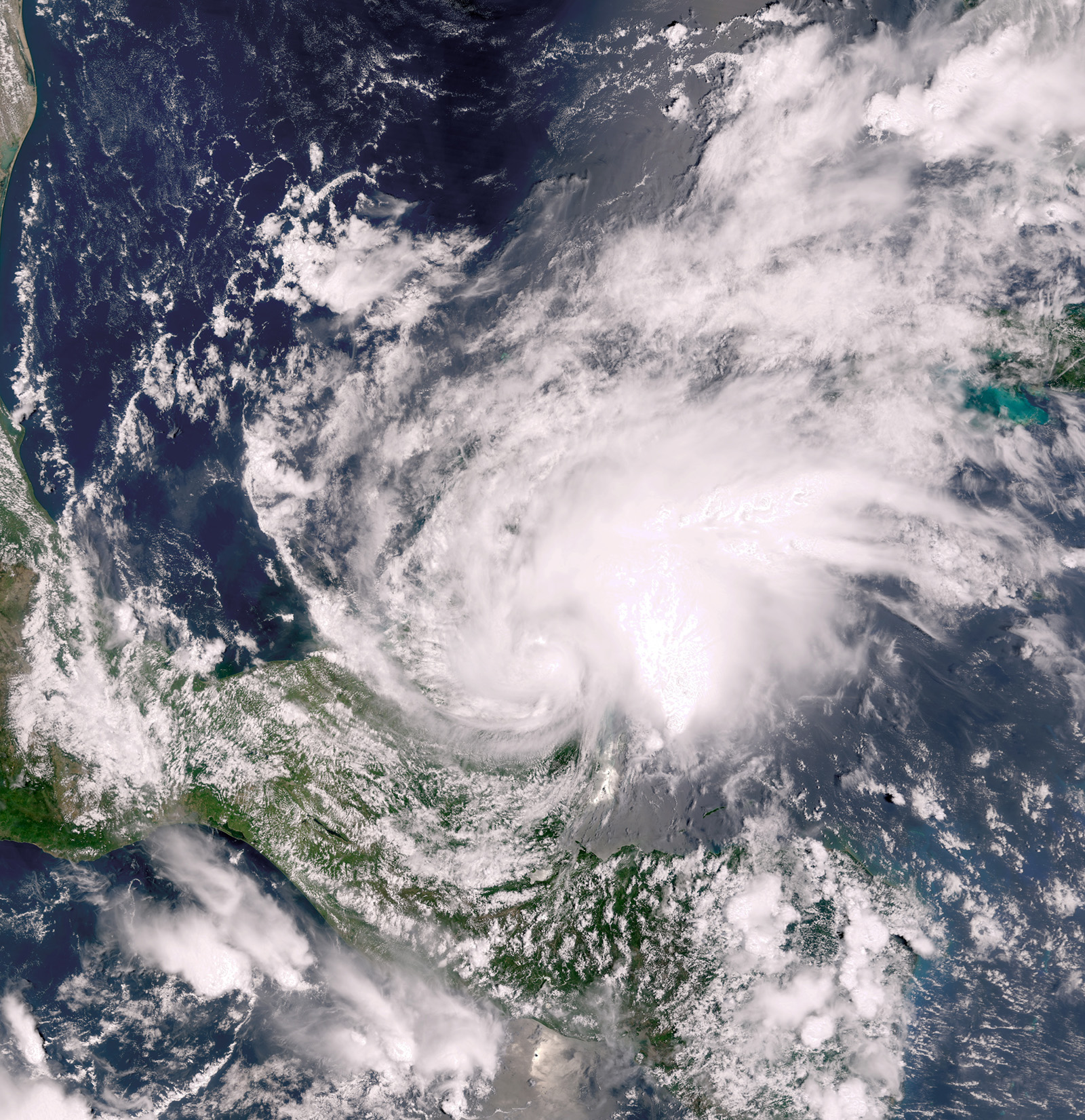

One of the snowiest winters in the US, New York flooded, Hurricane Arthur the earliest hurricane to hit in the Carolinas on record, the wettest Spring in England since 1797, the hottest summer in 150 years in Scandinavia – as they say in Yorkshire: “Weather we are having a lot of it”.

For the most part in our lives these natural events are perhaps fodder for a debate as to whether global warming is actually occurring (and the frustration with and of the insurance companies).

The natural crises in the developing world are usually, however, of a different order. You may recall the devastation last year in the Philippines of Typhoon Haiyan (did you remember the name?) – the lives shattered, up to 10,000 dead. As you looked into the eyes of the orphaned kids in the devastation of what was Teplocan at the time, was there ever a stronger moral case to be made for quick and effective grant making?

That storm of 2013 has now receded into dim memory along with the worse disasters of the 2010 Earthquake in Haiti that killed 300,000, or the tsunami in 2004 that killed 250,000, or the world’s costliest – the Japanese Tsunami in 2011 at a cost of $235bn (World Bank). Do we learn anything more about more effective aid as it disappears off the screens and blends with all the other philanthropic crises, or will we have a recurrence of the worst reports from Haiti and the tsunami when the next “natural” event hits? More seriously, do these crucibles of misfortune simply reflect the wider structural problems inside “modern” philanthropy?

Omens and anecdotes

The omens are not good and the historical anecdotes are legion. My own favourite was the relief package after the tsunami containing ski jackets and Viagra in Indonesia – a country with one of the fastest growing populations of 237 million, no snow and to my knowledge limited après ski. Or the windfall of fishing boats, a photogenic opportunity for Western aid marketing brochures but which has now resulted in overfishing. Or the pictures of the local populations pulling down houses built with aid, as they did not reflect local cultures. As Akash Kapur writing in Bloomberg noted about the tsunami: “It was clear that much of the outside world’s largesse was utterly removed from the needs and priorities of aid recipients.”

Equally, in a hard hitting article published at the beginning of this year in the Guardian on the third anniversary on the Haiti earthquake, a report by the Centre for Global Development, drawing from the reports of the UN Office of the Special Envoy (and with hundreds of thousands still today in tents, threatened by a re-emergence of polio and imported cholera, by the very people meant to help them), the report tersely notes:

“Official bilateral and multilateral donors pledged $13bn and…50% of these disbursed. Private donations are estimated at $3bn (together the equivalent of Haiti’s GNP).Where has all the money gone? Three years after the quake, we do not really know how the money was spent, how many Haitians were reached, or whether the desired outcomes were achieved.”

It goes on: “We found that about 94% of humanitarian funding went to donors' own civilian and military entities, UN agencies, international NGOs and private contractors. In addition, 36% of recovery grants went to international NGOs and private contractors. Yet this is where the trail goes cold… it is almost impossible to track the money further to identify the final recipients and the outcomes of projects.”

And here is the reality, not just related to disasters, that although we all mouth “multi stakeholder collaborations”, we have created a system where aid is allocated bilaterally creating gross inefficiency through lack of effective collaboration matched by a lack of transparency and accountability. At a broader level let me give you just one example: in the UN system you have 30 organisations involved in WASH (Water and Sanitation) where in many cases the funding decisions are made at a regional level – creating over 100 “demanders” of capital in the UN system in WASH alone. Add in the civil society, CSR, etc, and you probably have about 10 to 50 times that amount. All for the most part seeing each other as competitors for just one financial structure – unleveraged grant/aid funding. At the very best there is a loss of accountability.

Fragmented funding

On the funding side it is also equally fragmented and, as you can see in the Haiti example above, stove piped often by country. Each funder of course with their own agenda (as noted in the brilliant article of 2005 “Through the Looking Glass”, by Clara Miller, CEO of the Heron Foundation, comparing the “for profit” world and “not for profit” world. As Miller says: “You’re now back in the for-profit universe (having landed from Mars) and you’re the owner of a restaurant. Your paying guest comes to pay the bill, offers a credit card, and prepares to sign the charge slip. But before signing, the guest says, ‘I’m going to restrict my payment to the chef’s salary. He’s great, and I just want to make sure I’m paying for the one thing that makes the real difference here. I don’t want any of this payment to go for light, or heat, or your accounting department, or other overhead. They’re just not that important. The chef is where you should be spending your money!’”

Over all this “disaster” in both meanings stand the very dedicated folk at UN OCHA attempting to co-ordinate in disaster situations in 65 countries for which they have a 2013 budget of just $285m (provided by 44 donors of which to my earlier point 95% is voluntary funding). I was recently told that they have just started the process of strengthening the IT infrastructure to increase coordination. Now anyone who has ever managed an IT budget will recognise the scope of the challenge in this case, even if the whole budget was allocated to IT co-ordination which it is clearly not. UN budgets are notoriously difficult to decipher to outsiders but the 2012 allocation to information management for OCHA was $12.4 million. Those same IT folk will tell you that you need about 3-5% of total budget on IT systems in a system that has collaborative scale – so they hit that target but, relative to the expenditure, parties or issues they are trying to co-ordinate, well, as my teenage son would say: “Go figure.”

The role of impact investing

So, what is the role of impact investing? At Total Impact Advisors we have just completed some work for the Rockefeller Foundation on Resiliency as part of a new $100m programme just approved by their board – ergo strengthening the infrastructure prior to disaster. Our requested role is to identify the financial tools and solutions that could be applied to the issue of Resiliency.

At a systemic level, a lack of resiliency can be seen through five key market failures:

- Lack of savings/resources - Many poor individuals and communities lack access to financial resources, which inhibits their ability to save and invest in activities to promote their livelihoods, including spending on health and education. This is exacerbated in times of macroeconomic crisis.

- Lack of risk mitigation tools - Limited or no access to insurance or other risk mitigation tools, including forecasting, manifests at the micro-level as a lack of insurance options for the poor and at the macro-level as a dearth of larger-scale, more sophisticated insurance tools for key sectors of the economy, including financial services, agriculture, healthcare, and others.

- Lack of functioning domestic capital markets - Limited credit (at customer level and bank level) and liquidity in many rural and developing markets inhibits the ability to mobilise resources. Inability to align domestic capital markets in developing countries ($2+ trillion) with national development needs.

- Lack of economic activity - Limited access to financial or other resources creates a vicious cycle that inhibits the development of a commercial value chain and a functioning economy. The target populations are not integrated into the economic landscape.

- Lack of incentives to collaborate and scale - Lack of large-scale system of incentives for multi stakeholder collaboration. This prevents otherwise innovative tools from scaling and creates an inability to look at problems at a systemic level where the incentives are aligned for tangible, auditable social outcomes.

What is shockingly clear in the report is the lack of risk mitigation tools for households, communities, and countries reflected in:

- Limited private sector engagement: the private sector, while often engaged in disaster response from a philanthropic and business perspective, does not invest at the nexus of development and humanitarian efforts to prevent disaster;

- Inadequate use of big data: developing countries utilise outmoded methods to access, integrate and use crucial data and information to reduce vulnerability and risk, if they use data at all;

- Lack of evidence-based methodology: few players active in the field use rigorous methodologies to determine the resilience investments that matter most;

- Insufficient collaboration: Humanitarian and development actors rarely work together in a holistic manner.

One should add (albeit early days) that the report is part of a broader trend we see in the market. In looking at these issues holistically – as a systems issue – and then looking at these issues through the prisms of how a range of tools can be applied and recognising something we all intuitively recognise across philanthropy that we need inter and intra sectoral collaboration, which the current system patently and demonstrably fails to provide.

Challenges for many

Looking at the issues at a systems level raises challenges for many parties, even many in impact investing where current market thinking, it can be argued, has become fixated (some would even say self serving) on venture and private equity capital solutions. In reality the market is wider than this – it gets to the kernel of the debate about whether this is an ‘asset class’ or a range of financial and socially entrepreneurial innovation that can and should be applied.

The report also identifies what bankers would call ‘Alpha’ (and what normal folk call the “hidden value”) in impact investing. We christen this ‘ICE’ – Innovation through social entrepreneurship and social finance but critically also the “alpha” of Collaboration and Economies of scale.

Money is an incentive structure, so these incentives now need to be aligned with the delivery of financial structures that deliver auditable 'social' outcomes. This is the real promise of impact investing.

It is here that one also needs to look carefully at one of the shibboleths of impact investing – that we need metrics of measurement. Do we just measure the best of the current inefficient market – because as soon as light follows day the argument will soon follow that once we have a social “metric” (to the economists a segmentation of Indifference curves) then government should provide a subsidy.

However, if that metric is based purely on today’s inefficient market, what happens to the alpha of financial innovation, the alpha of economies of scale and the alpha of collaboration? This is potentially large – for example, in the GAVI framework – a $3bn + collaborative structure in vaccinations – this dropped the unit cost of vaccinations from $50 down to $5. In resiliency if we are to believe the Centre for Global Development, the benefits of collaboration, transparency and scale are probably even larger.

For the foundation world this raises challenges as well. On the capital side this is the transition from a 19th century banking system with foundations controlling $1 trillion in assets globally to a modern one – and aligning those assets with social mission. Then in simple financial product terms, using this capital to inject a range of capital market tools for social purpose: modern impact investing financial tools which will ultimately drive innovation, collaboration and scale to the benefit of a much larger philanthropic sector freed from its current, self-imposed capital crisis.

Resilience and disaster recovery in reality mask a broader crisis of management of large scale philanthropic / aid projects – the report to Congress on Afghanistan aid (published August 2014) again further underlined the point. Bilateral aid, in silos, in too many cases simply does not work; money is an incentive structure, so these incentives now need to be aligned with collaboration, scale and the delivery of financial structures that deliver transparent, systemic auditable “social” outcomes. This is the real promise of impact investing.

Now, some will say reading this that these words threaten the flow of aid to those orphans. But in moral terms and indeed realpolitik terms our current stance is like offering a band aid to an orphan child (or a ski jacket in Indonesia) and failing to invest in the tools that can create real change for their children.

The report – and it is only a first step – is about noting the tools in the tool box that can be used. The real question is, do we have the will to implement and use them?

The fault dear Brutus lies not amongst the stars but amongst ourselves.

Link through to the Rockefeller report and blog here.