Turkey’s social enterprises have “exciting potential”

The latest research into social enterprise in Turkey finds a small but rapidly growing sector, working in areas such as improving education and supporting refugees. Yet more recognition is needed for social enterprises to truly fulfil their potential.

Social enterprises in Turkey are gaining momentum and have exciting potential, according to new research published by the British Council.

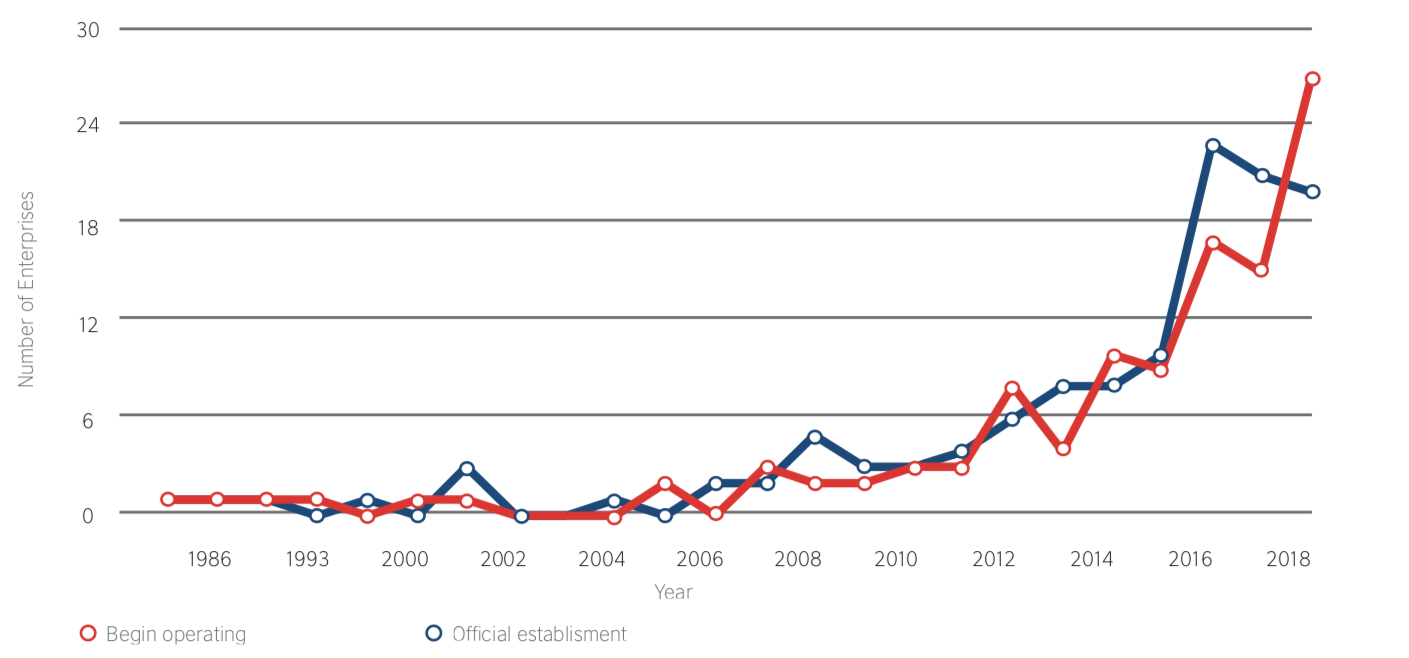

The State of Social Enterprise in Turkey, published this summer, describes the small sector of 9,000 social enterprises as “vibrant” and “gaining momentum”, particularly since 2015. (By way of comparison, Malaysia, with a similar economic profile, is estimated to have more than 20,000 social enterprises.)

In fact, the landscape in Turkey is changing so rapidly that the team of researchers struggled to keep up while they were carrying out the study. As they were compiling their catalogue, “each week one or two entirely new social enterprises would be added”, they write.

There has been a significant increase in the number of social enterprises being established in Turkey since 2015

There has been a significant increase in the number of social enterprises being established in Turkey since 2015The research notes that intermediary organisations are expanding, new actors are entering the field and the number of social enterprise-related events are growing. As a result, the researchers caution that due to this intense activity, the data will not stay up to date for long, but should rather serve as a baseline

In the report’s foreword, the British Council’s Turkey director, Cherry Gough, said that while visibility and public understanding of social enterprise was still limited, the report revealed its “exciting potential”. She added that the research shows the sector was “vibrant and increasingly diverse”.

The sector is flourishing despite particularly difficult circumstances. In 2016, according to The Best Countries to be a Social Entrepreneur which surveyed perceptions of 20 experts in each country and was conducted by Thomson Reuters Foundation and the Global Social Entrepreneurship Network, Turkey was ranked last out of 45 countries. The country fared particularly poorly on points such as government support and public understanding of what social entrepreneurs do.

The research points out a number of obstacles, including not only practical challenges such as accessing finance and support but also the difficulties generated by escalating tensions across the region. Turkey is bordered by Syria, Iran and Iraq and it is now home to around 4m refugees – the largest global population of refugees – including 3.6m from Syria alone. While social enterprise can be a powerful tool to support refugees, without strategic direction and co-ordination, the opportunity for social enterprises to act in this area may be missed.

Turkey’s economic landscape has also suffered instability and it is just emerging from the latest recession which hit at the end of 2018.

Raising awareness is key

Berivan Elis, manager for the Istasyon TEDU Center for Social Innovation, who led the report’s research team which was supported by Social Enterprise UK, says that a lack of visibility and awareness of social enterprise was a major finding of the research, with a lack of understanding among public institutions reported as “an important barrier” by 80 per cent of respondents.

“If there is awareness and visibility, access to finance and support mechanisms will become less of a problem,” she says.

“There are no official statistics pertaining to social enterprise in Turkey. No study on the estimated number of social enterprises was done before. Turkey was not covered in global reports publishing data on the subject,” says Elis. This report aims to go some way towards plugging the information gap while raising awareness at the same time.

Duygu Vatan, co-founder and operations manager of social enterprise Joon, believes more visibility and public awareness of what social entrepreneurship means not just among public institutions but also among communities will lead to a “snowball” effect.

Elis says there are numerous ways people are trying to achieve more awareness about social enterprise, both among public institutions and the wider public.

“Some ecosystem actors are lobbying the government for more support,” she says, while others are working for further visibility and support in the private sector. There are also “newly established networks of intermediary organisations conducting policy dialogue meetings with public officials.”

The report says that raising media awareness is necessary for the sector to further develop, and calls on everyone involved in the sector to work on enhancing “the visibility of the work of social enterprises and to spread the social enterprise concept to the general public”.

Tackling the education “sore spot”

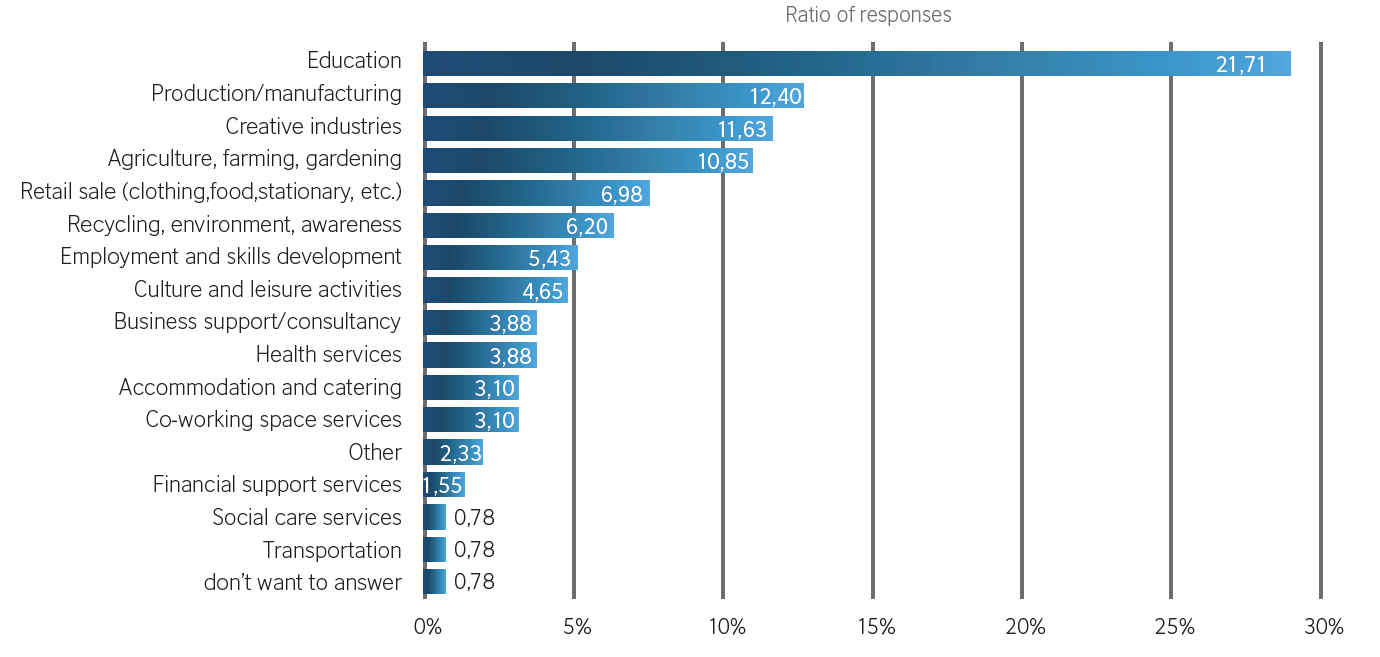

The top motivation factor participants gave for starting an enterprise was “a problem that I personally or people close to me experienced”; education (accounting for nearly 22%), manufacturing (12%) and the creative industries (12%) were the most common sectors that social enterprises worked in.

Elis says education is a “sore spot for everyone in Turkey”, with big gaps in access among regions. Many people in the country have lost trust in the education system after frequent changes to the system, she says, and this makes it a popular focus for social entrepreneurs. Initiatives have been set up for children with special educational needs, such as maths education for deaf children or creating digital content for children with autism, while other social enterprises address vocational training, lifelong learning opportunities and digital literacy.

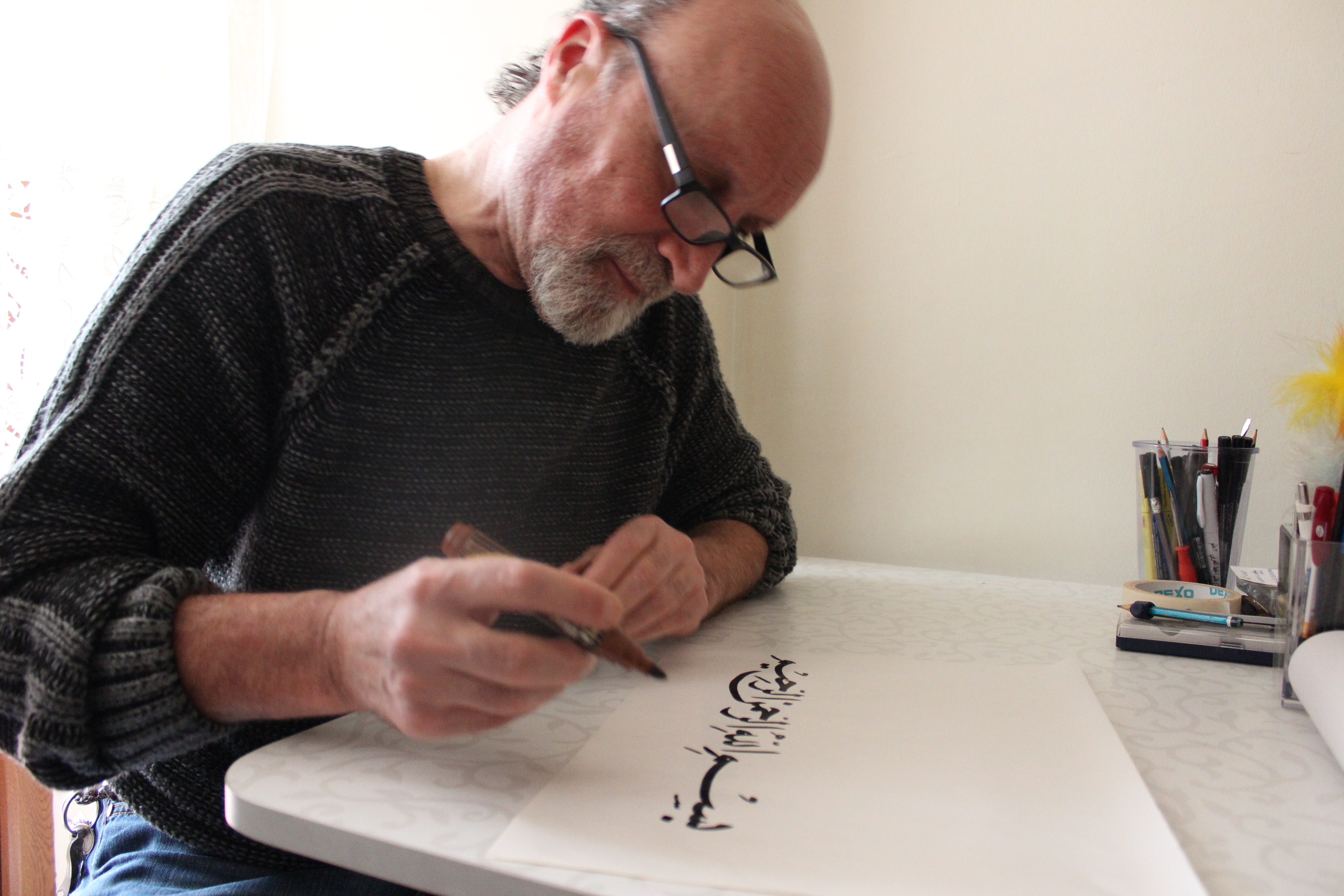

Vatan co-founded Joon, a platform supporting craftspeople from disadvantaged backgrounds – including refugees – in 2016. One of the first people the enterprise collaborated with was a Syrian calligraphy artist, named Mr Tawfiq (below), who produces a collection of home and personal accessories such as lamps, posters and notebooks drawing on “words that inspired him in his migration journey”. She says that thanks to that work, Mr Tawfiq has since received custom orders and now provides calligraphy courses to people in his neighbourhood. This work, she says, “illustrates the right combination of people and networks can change one person’s life.”

An opportunity for women leaders

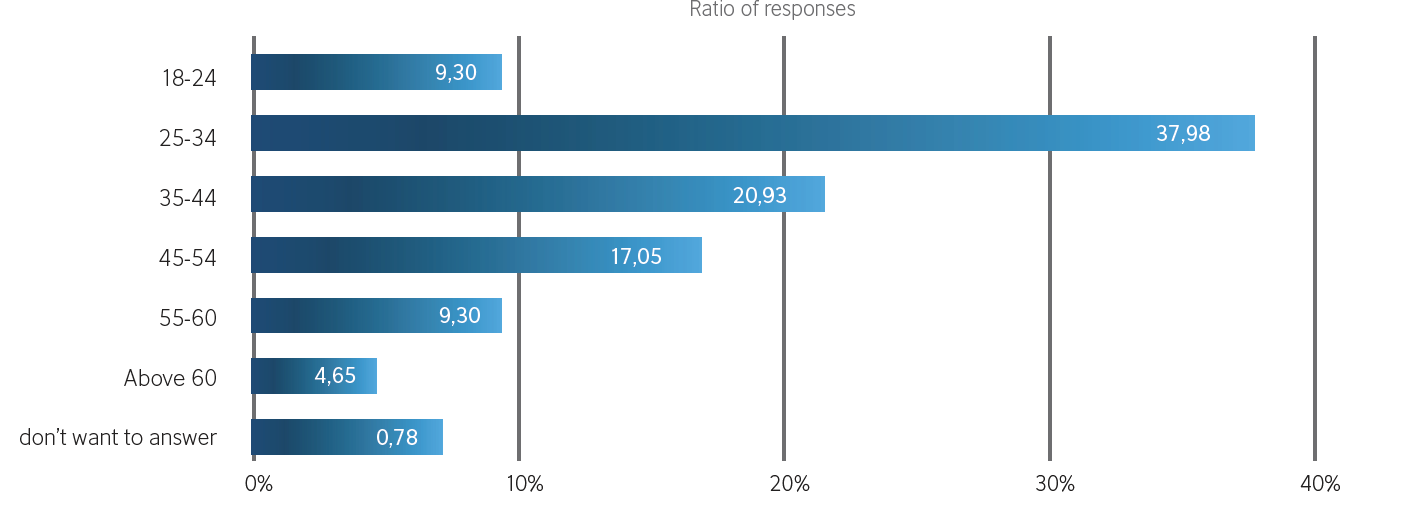

Leaders within the sector tend to be young with almost half (47%) under the age of 35 and more than half (55%) of enterprises founded and managed by women. This figure is particularly striking, point out the researchers, when contrasted with female leadership in conventional business and civil society organisations in Turkey which stands at just 19% and 14% respectively.

Elis says this finding is in line with the global situation, where “women leaders make up half of the leaders of social enterprises across the world”. Many of the people starting Turkish initiatives are highly educated, she explains, with 84% of founders holding a degree and 20% holding masters or doctorates.

The researchers comment that as social entrepreneurs tend to be relatively young, educated people, living in major cities in Turkey, “it appears that social enterprise is being driven by a relatively privileged social group”.

Elis explains that well-educated women in Turkey often “follow global trends closely,” and are inspired to start their own initiatives. “Women get into the world of social enterprise when they see other successful women role models,” she says. One reason more Turkish women are being drawn to the social enterprise sector is that, for many, “conventional jobs do not offer enough self-realisation opportunities or autonomy”, she says. Gender equality in education and the workforce continues to be problematic in the country. In 2018, the World Economic Forum ranked Turkey 130th out of 149 countries in its Global Gender Gap Report, citing a large gender gap in labour force participation as well as wage parity for similar jobs for many educated women.

Vatan agrees. She says being born a woman in Turkey means facing disadvantage from the very beginning. “In your house, neighbourhood, school, you are not treated equally as men,” she says. “You cannot get a ‘men’s’ job, for example. Or even worse, your safety is a big concern. As a response, you are naturally an innovator.”

The reason so many women are drawn to working in social enterprise, is “because we know that we can make a change. And we have to,” says Vatan.

“When you never become a part of any wheel and the system is the main reason for that, you learn how to make your own wheel and become the pioneer for the movement of change.”

Header photo: Joon

• Interested in global social enterprise research? Check out our coverage of the British Council's extensive collection of reports here.