Why profit-driven business can never be the answer: Exclusive interview with WFTO boss Erinch Sahan

Is the key to climate change our business models rather than our buying habits? DICE Young Storymaker Julia Cass Hebron interviews Erinch Sahan, CEO of the World Fair Trade Organisation, about the role of social enterprises and sustainability in consumer choices today.

Erinch Sahan is a firm believer that the traditional, profit-driven business model has had its day. Not only are alternative, more ethical structures desirable – but they are eminently achievable, says the CEO of the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO).

He’s in a good position to know. Before taking up his present role, Sahan founded the Future Business Initiative at Oxfam in the UK, a role in which he led the charity’s work on promoting fairer models of business. Prior to this, he was employed by the Australian Agency for International Development, after gaining degrees in finance and international business, and in law.

I’m interviewing Sahan as part of my research into another feature on eco-anxiety, for the DICE Young Storymakers series on Pioneers Post – and he has plenty of wisdom to share.

We start by discussing the behaviour of shoppers over the last few years. What have consumer attitudes been like? Have they changed?

He says there’s a rising tide of ‘green consumerism’ and shoppers concerned about the ethics and sustainability of the products they’re buying. But people are slow to change their shopping habits to reflect their values. “Except ‘deep green’ and Fairtrade consumers, in the broader economy [statistics indicate] 90% of consumers have no willingness to pay more for sustainability,” he says.

90% of consumers have no willingness to pay more for sustainability

Given the global acknowledgement of the climate crisis, this seems like a depressing figure – but Sahan believes that pushing the needle of consumer behaviour is possible. One key to shifting shopping choices is information and providing more ethical alternatives in the aisles, he says. “When you reach a product in a shopping aisle and remember something negative about the brand, people will buy an alternative,” he believes, pointing out that Fairtrade has experienced considerable success over the last half decade and now the Fairtrade mark is recognised by 90% of UK shoppers.

But why are consumers so slow to change? Is it lack of information about the alternatives available, scepticism of sustainable claims, or something else?

Sahan says all these factors play a part. Greenwashing and eco-anxiety – the phenomenon of people suffering symptoms of anxiety including mental paralysis, sense of doom and helplessness – lead to consumers being less willing to trust company claims.

At the same time, we are all used to a world in which the idea of success is focused around private gain: “The systemic problem is an economic system that is designed to be obsessed by economic growth and populated by businesses driven by profit maximisation at any cost,” he says.

This is “the key driver behind the problems”, Sahan believes. “Greenwashing is there, and people should be sceptical and very conscious that it’s the cheapest way for businesses to retain consumers.”

Sahan says the tide of consumers driven by ethical choices is definitely rising. This is illustrated by those ditching plastic in the supermarkets, looking for ethical certification and supporting local producers.

But such factors that might seem to be intuitively more sustainable can be misleading. For example, in Kenya export horticulture (vegetables and flowers) provides up to 2 million jobs and is a major earner of foreign exchange. The positive benefits felt by small-scale producers and rural economies included in this supply chain have been shown to outweigh the negative impact of the ‘food miles’ incurred.

In the light of all this confusing information and consumer scepticism, how can social enterprises retain customer trust and address their concerns? For Sahan, it comes back again to the business models. Conventional, profit-driven businesses will never be sufficient to create an environmentally, socially or economically sustainable future, he claims.

We must “move consumers away from these plastic / palm oil questions”, he says, because companies can respond to such concerns yet “still do a million things that are damaging the planet like incentivise deregulation of land use”.

The answer lies in supporting social enterprises that will then serve as examples that a people-driven business model is not only an ethical alternative to conventional business models, but an achievable one.

“By definition the mission [of social enterprise] is to maximise social or environmental benefits,” he says.

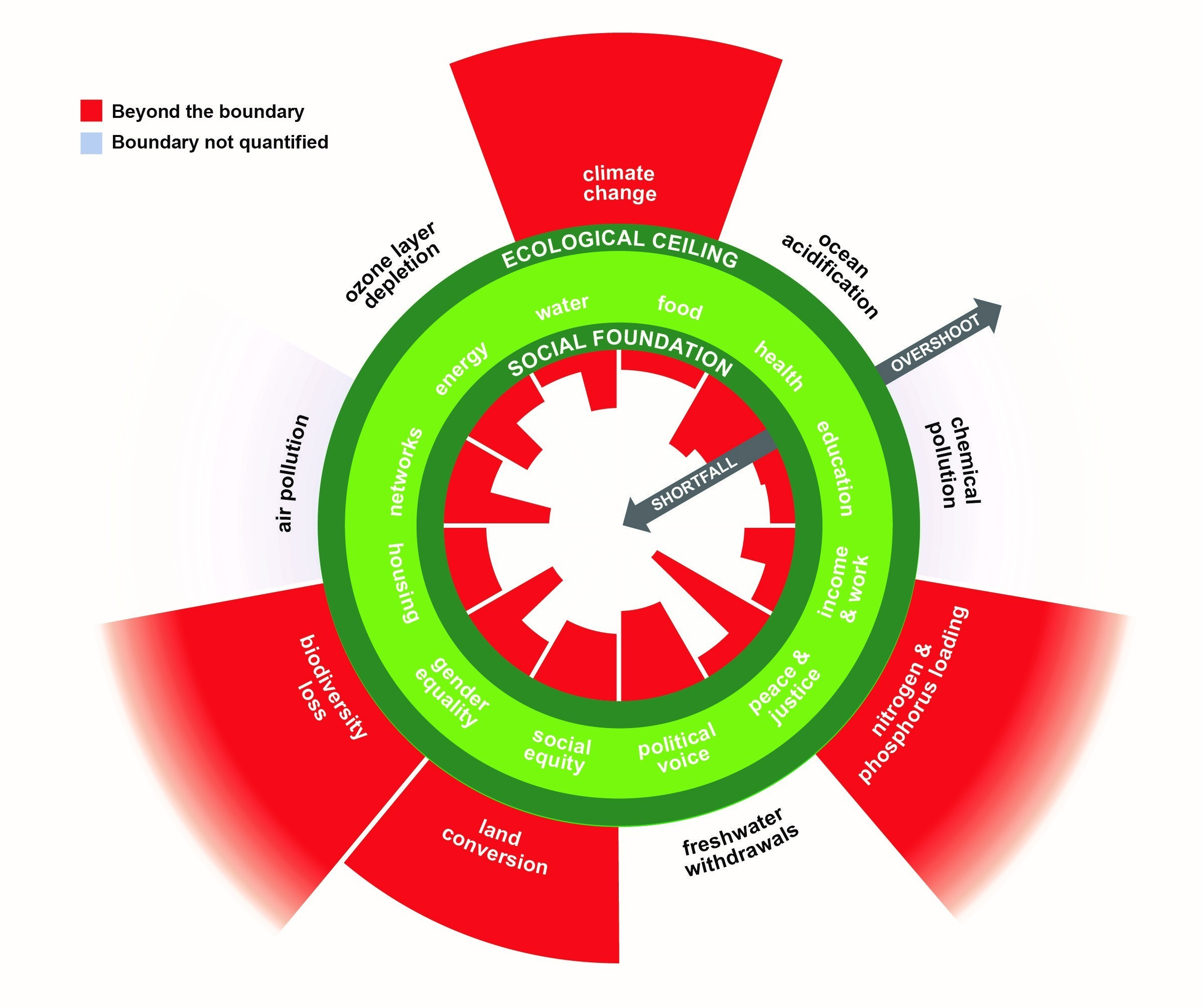

Sahan also cites so-called ‘doughnut economics’ (see illustration below) to explain the importance of maximising the social and environmental benefit of each spending decision. “There’s a planetary boundary and a social floor and we need to stick between the two,” he explains. “We need enough economic activity for dignified livelihoods for the basics of human life to be sustained. At the same time, the planet can only give us a certain amount because the economy has a carbon footprint.”

Doughnut economic theory pictures the environmental and social boundaries of the earth's resources as a 'crust' which we cannot overshoot if we want to maintain a sustainable society. At the same time, many people live in the 'hole' of the doughnut where they lack some of the earth's essential resources - like clean water or political freedom. The challenge is to make sure that we help everyone escape the 'hole' without overshooting the limits of the earth's resources in the process. Image: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier/The Lancet Planetary Health

So how are the two reconciled? A consumer should aim to make sure each pound, dollar or euro they spend maximises social impact and minimises environmental impact. For example, “by spending money on things from businesses that employ more people, that are labour-intensive not capital-intensive. Putting to work carbon footprint that maximises social benefit.”

A consumer should aim to make sure each pound, dollar or euro they spend maximises social impact and minimises environmental impact

So if social enterprises are the answer, how can they communicate their difference from conventional businesses? It’s well-known that social enterprises can struggle to have the capacity to promote themselves next to some of their big, commercial competitors.

“The WFTO movement needs to communicate about who we are and what we do. If we communicate every time we’ve started a world-leading practice and it catches on with consumers, that specific practice will be replicated by mainstream companies, but they’ll get rid of the things that don’t maximise profit. They’ll cherry-pick,” he warns. “We need to focus on a social enterprise movement – communicate who we are, our profit distribution models,” he says. “As consumers, we shouldn’t be satisfied with the status quo of social injustice and ecological collapse.” However, ultimately, “until we change the business paradigm I can’t see a future with a positive outcome.”

The most important question, then, is will it change? And will it change in time?

Sahan can’t predict the future of consumer behaviour but ends on a hopeful note: “Social enterprises will continue to grow around the margins but we’ll reach a tipping point where we have to say that we have proof of concept. We can then be louder in proclaiming, ‘We’re not filling the gaps, we’re the retailers and companies of the future’.”

Erinch Sahan is speaking at the Social Enterprise World Forum this week in Addis Ababa, in a session on 'Consumer choices – market positioning and marketplaces'.

Julia Cass Hebron is a DICE Young Storymaker – one of fourteen young journalists recruited by Pioneers Post and the British Council from six countries to report on social and creative enterprise. Read more of their stories here.