Creative, resilient and innovative: why governments can no longer afford to turn a blind eye to the informal economy

Millions of craftspeople and artists across the globe work in the informal economy, some choosing to sacrifice security for freedom and creativity, others making a living the only way they know how. Now is the time to explore how to support them better, believe campaigners, so more people can enjoy good, secure jobs while they bring vibrancy and stability to their communities.

Across the world, millions of craftspeople and artists go to work every day. Through weaving, photography, performances and more, they earn money to support their families, and they keep their communities buzzing.

But in their governments’ eyes their jobs don’t exist. While they might make a good living day-to-day, they don’t have the social protections that many other people take for granted, like sick pay and workers’ rights, and they struggle to get credit or open bank accounts.

These people are part of the informal creative economy – a huge part of our global economic system which, campaigners say, policymakers must not continue to ignore if sustainable development is to become a reality.

We are wasting so much creativity, wasting so much innovation

The UK Policy and Evidence Centre International Council, a global network of academics and policy and creative economy practitioners convened by the British Council, undertook research last year to explore the intersection between the informal economy and the cultural sector in the global south, as well as the experiences of those who work in this space.

Speaking about the research at The Missing Pillar Global Talks: Common Sense and the Community, an online event led by the British Council held in March, the PEC Council’s chair, John Newbigin, said that the informal creative economy was vital to the cultural vitality and sustainability of communities, yet it was largely ignored.

The research, he said, highlighted lessons for practical actions that governments, civil society and the financial community across the world could take to improve millions of people’s lives.

He said: “We are wasting so much creativity, wasting so much innovation, and putting so many lives that do not need to be at risk and have got great potential, in a position where they are at risk and very often are unable to realise their potential.”

Fragile as well as resilient

According to the International Labour Organisation, two billion workers – representing just over 60% of the world’s employed population – are in informal employment. Although the informal economy exists in developed countries, it’s more prevalent in developing countries, and, according to the PEC International Council, the proportion is almost certainly higher in the creative and cultural industries.

Avril Joffe, cultural economist at the Wits School of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, and member of the PEC Council, explained that workers in the informal economy are “outside the purview of the state and therefore they have no access to any of the social protections that come with the definition of being an employee”, such as maternity benefits and unemployment protection.

It is a sector that is both very fragile, because it is unprotected and largely unknown, but at the same time, extraordinarily resilient

What’s more, highlighted Newbigin, informal workers are vulnerable to exploitation, and they find it difficult to access finance and markets.

The Covid-19 pandemic, said Newbigin, highlighted the importance of the informal creative economy. “It is a sector that is both very fragile, because it is unprotected and largely unknown, but at the same time, extraordinarily resilient,” he said. “Because when all the regular structures of financial and state support began to come under pressure, it was the informal activity in communities that sustained communities.”

The pandemic also exposed the vulnerabilities of these workers, as they fell through the safety nets put in place by some governments, such as furlough or other employment support.

He added that informal creative workers “feed the solidarity” of their communities and are crucial to communities’ cultural vitality and sustainability.

An untapped goldmine in India

200 million people in India depend on craft for their livelihood, and they are an “untapped goldmine for sustainable development”, according to 200 Million Artisans, an organisation that aims to boost this informal economic group’s recognition and success.

The organisation claims that these artisans are not only India’s heritage but also the country’s “global competitive advantage”, with the potential to ensure the wellbeing of its young people, women and diverse communities.

200 Million Artisans was founded in 2020 in response to the pandemic. “We realised that many artisan communities did not have support, as the government’s focus was elsewhere,” said CEO Priya Krishnamoorthy.

Lack of proof of their impact is one of the biggest challenges to increasing recognition and support for India’s artisans. “There is no evidence that says that this sector creates impact,” said Krishnamoorthy. “There is no evidence that says that there is potential for growth.”

While official figures talk about 7m artisans, she said, many researchers estimate there are as many as 200m artisans. They are mainly found in traditionally marginalised communities in isolated rural areas of India. The workers don’t have insurance, bank accounts or ID cards, and they are predominantly women.

“That’s a massive policy gap for us to ignore,” said Krishnamoorthy. “We need to start talking about these communities and addressing what their challenges are.”

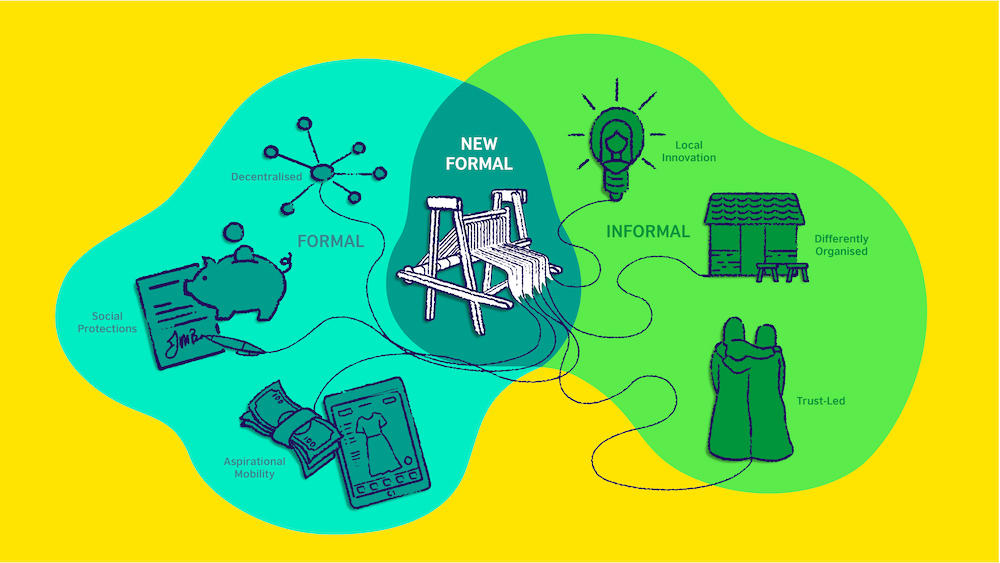

200 Million Artisans undertook research to explore how some of the country’s creative workers earned their livelihoods. They discovered a phenomenon that they called the “new formal”, a hybrid model of enterprise that combines some of the positive aspects of informality, such as flexibility, decentralisation and worker ownership, with benefits from formal organisations, such as social protection and financial inclusion.

Rangsutra, for example, was founded in 2006 with seed funding from 1,000 artisans to bridge the gap between artisans and the markets. Now it has more than 2,000 shareholders – they are craftspeople all over India who weave, embroider and dye fabric; 80% of them are rural women. The company supplies big corporations, including Ikea, and its artisans have sustainable incomes, decision-making power in their enterprise, training and safe working environments.

“You have to customise solutions for the community, you have to meet them where they are. That is how we drive true inclusion,” said Krishnamoorthy.

Informality or innovation?

200 Million Artisans was just one of the examples in the PEC Council’s research which investigated the lives of creative people working in the informal economy all over the world – as photographers, scriptwriters, craftspeople and more. The aim was to highlight the huge social and cultural impact of their informal work.

“I think we all need to recognise – any stakeholder truly invested in driving sustainability – that the world is a global village now, that the only way forward is to learn from each other,” said Krishnamoorthy.

People working informally are part of this abundance and vitality that we so cherish in our daily lives

“Every big step of innovation in the economic and social system starts with parallel systems of production,” said Dr Leandro Valiati, PEC council member and lecturer in arts and cultural management at the University of Manchester. “You can call it informality. But you can also call it innovation.”

Avril Joffe said: “People working informally are part of this abundance and vitality that we so cherish in our daily lives. So governments need to really ask, can they afford to ignore the incredible output that is coming from this part of the economy? Can they afford to not count the contribution that is being made, not only economically but socially – in forms of inclusion, in forms of community participation, making our cities more vibrant. Can they afford to ignore that?”

Header photo: Some of the Rangsutra artisans, who have social and economic protections thanks to the way that their organisation is structured. Image courtesy Rangsutra

• Explore the Missing Pillar talks further in this series of films.

Thanks for reading Pioneers Post. As an entrepreneur or investor yourself, you'll know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our subscribers to sustain our journalism – so if you think it's worth having an independent, specialist media platform that covers social enterprise stories, please consider subscribing. You'll also be buying social: Pioneers Post is a social enterprise itself, reinvesting all our profits into helping you do good business, better.