The devil in 'investment opportunities': Why funding solutions must be the new paradigm in impact investing

Seeking impact investing ‘opportunities’, no matter how thorough our search, will always mean a focus on targeted returns for an investor, with impact a secondary interest, argues the European Investment Fund’s Uli Grabenwarter. That also means little incentive for intermediaries to go the extra mile or think creatively to develop funding for the most vital projects. In the latest in our Impact Papers series with EVPA, we are told it’s time to turn our thinking on its head: here’s how...

In October 2018 the Global Steering Group for Impact Investment (GSG) published its report on impact investment wholesaler organisations, making a case for the role such wholesalers can play in catalysing money for impact. The report explores various means of intervention, from grant-giving to for-profit investment. It addresses the challenges of fundraising from different stakeholder communities, while reflecting on the constraints related to different sources of capital. As such, the report is a welcome stocktake of market practices and first experiences in this field.

However, this report remains silent on the biggest unresolved question of the impact investment movement: how to get capital to impact rather than getting impact to capital?

This isn’t just a clever play on words; it’s at the very basis of what prevents impact investing from becoming a true catalyst for change.

Impact investing conferences all over the world celebrate ever-increasing amounts of capital mobilised for impact. Yet, the number of societal challenges appears to increase at an even faster pace.

Why has impact investing failed so far to have a visible impact on these challenges to our society? How can the impact investing community still complain about the lack of ‘investment opportunities’ to deploy capital while thousands of issues still wait to be solved, and their possible solutions lack funding?

Back to basics

The answer to this intriguing question may very well be in the concept of impact investing relying on ‘investment opportunities’.

It is about time we realised that the vast majority of ‘impact investors’ seem to ignore the central requirement of any impact investing approach: how can we be impact investors if we delegate to a third party asset manager the decision on what impact we seek to create? How can such impact, which depends exclusively on the preference of such opportunity-driven managers be an intentional part of our own theory of change as a mission-driven investor?

Impact investing is not about investing in opportunities. Impact investing is about funding solutions.

How can we be impact investors if we delegate to a third party the decision on what impact we seek to create?

Our financial system is densely populated with players who are ready to invest in opportunities. But where are the intermediaries who transform social and environmental challenges into precisely those investment opportunities – ones that not only satisfy a specific risk-return profile but equally provide for positive outcomes?

In the wide universe of impact investors and market intermediaries, so far none has stepped forward to take this on. Why is this?

Undoubtedly because, in the functioning of our entire financial system, there is no reason why anyone should do so. What would motivate a mainstream investment manager to be selective on the impact achieved through its investment portfolio, if demonstrating just any type of impact already mobilises enough demand for its products?

Even impact-centric investment managers (social venture funds, sustainability funds, microfinance funds, and so on) merely look at a universe of opportunities in need of funding and select those that fit the risk/return requirements of the capital they invest. But who is looking at those opportunities that, at first, don’t ‘qualify’ and yet might be pivotal in solving our biggest societal challenges?

Inverting our thinking

In response to this, I hear some arguing that we are talking about investment here, and not about charity: “Let’s not mix concepts!”

Others will say: “Mainstream capital just cares about an opportunity to generate return. Which is fine, and if it creates some impact as a side effect then that’s great, but let’s not mix concepts!”

And then there are those players who reportedly do nothing else but impact – development finance institutions (DFIs), big foundations, impact investment wholesalers. Year after year they publish impressive figures on how much money has been invested responsibly in sustainable projects and groundbreaking innovation; how much CO2 footprint has been reduced; how many people have been lifted out of poverty, and so on.

But how many problems have they actually solved?

And let us assume there are a number of problems that actually have been solved by their intervention: who decides on the priorities within these problems to be addressed – and based on what? Is it really the urgency of the problem? Is it the scale of the problem? Or is it the ‘eligibility’ of the project? Or perhaps the ‘opportunity’ to fund it?

We need to find ways for investing in impact necessities

The problem we are facing is not a shortage of opportunities for investing with impact. Justifying well-intentioned use of capital today is no longer difficult.

The true difficulty arises from the fact that the benchmark for impact that is needed has moved: identifying impact investment opportunities is no longer good enough. We need to find ways for investing in impact necessities. Such an approach may very well require inverting our thinking.

Think about how we need to move from asking questions like, “How much CO2 output have we cut from air traffic this year?” to questions such as, “How can we make air traffic between European capitals redundant?” The same shift is needed in the financial world – from the question of, “Where can we place impact-conscious capital?” to questions such as, “How can we ensure a given impact project has access to the capital it requires to materialise?”

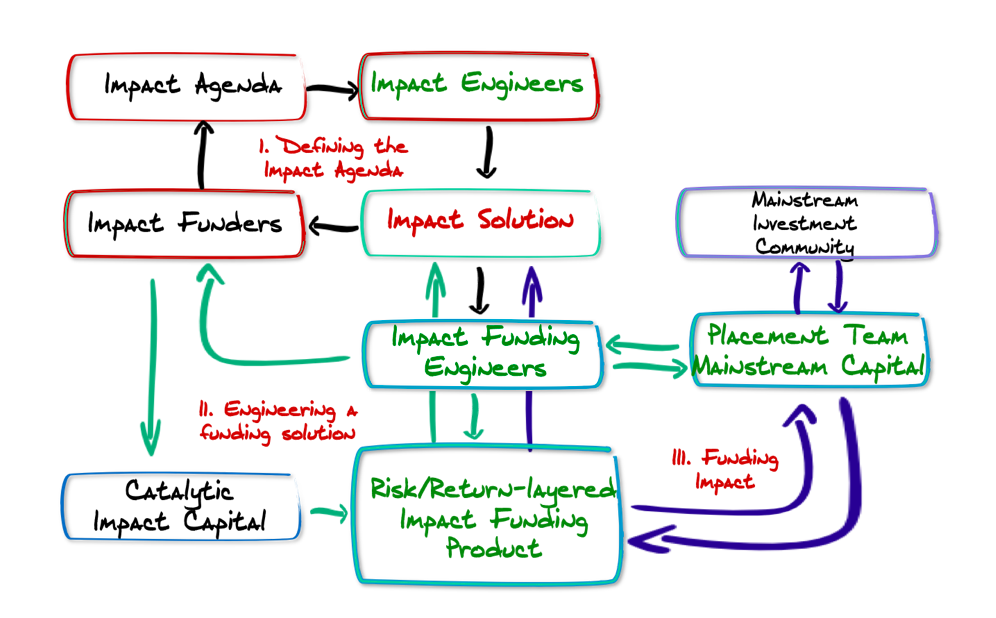

A new impact value creation chain

To achieve this and to get impact action funded, a new type of intermediary seems to be required. Intermediaries with the vocation of engineering funding solutions for impact.

Where would these new intermediaries come from? As for any market actor, there needs to be demand for them, and such demand can only come from an increased awareness and increased ambition of investors who care for impact.

Let us look what such an impact value creation chain could look like.

As a starting point, we need to identify those in the impact investing community who pursue impact not just opportunistically as an eligibility criterion in their investment approach, but those who are binary about the impact they want to achieve: “Give me a solution that creates that impact or you won’t get my money!”

Impact agenda:

It is an impact agenda at the beginning of an investment process which characterises such an approach.

If, as an investment community, we are not able to articulate what impact exactly we want to obtain, and what change we want to bring about, it is unlikely that the coincidental combination of market forces and stakeholders’ interests will yield a theory of change that credibly articulates our impact agenda.

So here is the first insight we need to accept as impact investors: an impact investing opportunity, no matter how great our patience to wait for it, no matter how thorough our search for it, will not be designed to meet an impact objective but will always be designed to meet the return objective of the investor community it targets, with any impact being a – surely intended – side product next to the financial return.

Yet, we can no longer afford to rely on by-products of financial value creation for the sustainability of our society.

And we surely cannot count on the hope that, in the time left to secure our very survival, the ‘right’ opportunity to invest in will knock on our door.

Impact solution:

Any impact agenda then needs to be transformed into an impact solution: a project, an activity, or a series of projects or activities executed by one or several actors acting independently or together towards achieving a predefined impact, reflected in the asset owner’s theory of change. Such translation of an impact agenda into an impact solution does require sector and technology expertise as well as knowledge of the geographic and political context. In short, very much the expertise national and supranational DFIs would have.

Once such an impact solution is defined, it will need to be tested for feasibility: are the actors needed to achieve the desired impact available? Can any complementary skills needed be brought together in a coordinated way that makes the desired end result achievable? Are the actors prepared to engage in implementing the solution? If yes, what is the most efficient way with the highest probability of success to achieve the desired outcome? And finally, how much does it cost to implement that solution?

As much as this chain of thought should apply to any impact agenda in an investment process, it is obvious that it becomes increasingly complex as the scale of ambition increases. The main Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for ‘impact engineers’ would look at the success rate of their impact solutions both in substance and in scale and assess the credibility of their proposed solution for attracting the necessary funding.

Impact funding engineers:

Just as it requires true engineers to craft solutions that meet technical targets, it requires impact funding engineers to craft financial solutions that can secure the funding of impact solutions at scale.

This is thus the second group of actors which is largely missing in today’s impact investing offer. Rather, the financial system is full of scouts identifying impact investment opportunities for a community of investors who seek to achieve some type of impact. Yet, as long as investment opportunities in the market sufficiently satisfy investors’ demand for some kind of appealing impact that generates the right level of return for the right level of risk, existing intermediaries will have no incentive whatsoever to go the extra mile and develop the creativity needed for funding projects that have a pivotal importance for the sustainability of our society.

Existing intermediaries have no incentive to go the extra mile and develop the creativity needed for funding projects of pivotal importance

A true impact funding engineer, if placed within an impact wholesaler, would consequently be assessed against two main KPIs:

- The extent to which they succeed in developing a funding concept that can effectively secure the capital needed to implement the impact solution; and

- The amount of concessionary capital (i.e. capital ready to compromise on returns for securing the impact) required to mobilise sufficient mainstream capital for funding the impact solution.

Funding impact in mainstream markets

The KPI assessing how carefully concessionary capital has been used by impact funding engineers to craft financial products should be a shared KPI for assessing the performance of the placement team for mainstream capital. Typically, the placement force for selling impact products in the mainstream markets should have a say in what is placeable and what is not. At the same time, they must however be equally incentivised to use concessionary capital in the most economical way.

Selling an impact funding product at conditions that outpace any alternative in the financial markets is not a science. Like an investment bank’s performance which is measured by the lowest cost of capital it can secure for a project or company, the performance of the placement team for impact investment products in mainstream markets must secure the lowest cost of capital for the impact solution to be funded. Such cost of capital is not only assessed by the return paid to mainstream investors but also by the use of the most ‘expensive’ funding source in any impact investing context: the use of the scarce resource of concessionary capital.

Will it ever happen?

As intuitive as it may sound, will the above described chain of funding ever materialise – or will capitalism, which looks at individualised profit maximisation only, prevent such evolution?

Due to the current lack of incentives, mainstream markets will not be the natural catalysts for such a change.

However, recent examples show that impact-driven stakeholders can evolve into such a role that catalyses capital for concrete impact solutions.

Earlier this year the MacArthur Foundation in the US launched a tender of $150m in catalytic capital to help fund ideas that help address critical social challenges.

Similarly, the African Development Bank has launched the Desert to Power Initiative which will connect 250 million people in some of the world’s poorest countries in the Sahel region to electricity from solar energy, 90 million of whom will be connected to electricity supply for the first time in their life. In this case, the starting point was not to consider which project could be funded, but rather the question of how a population deprived of access to energy could be connected to the electricity grid.

These examples show how DFIs, foundations and others equipped with concessionary capital can unite their forces in setting pivotal national, regional and global impact agendas and – with their capacity to take risks – mobilise mainstream capital. If others can follow examples like these, then we may very well stand a chance of winning the race against time.

Uli Grabenwarter will be speaking at the EVPA's 15th Annual Conference, Celebrating Impact in The Hague, 5-7 November. At the conference a major new document, the EVPA Charter of investors for impact, will be presented, sharing key principles that drive and distinguish investors for impact.