‘Pracademics’: a new generation of academics who walk the talk

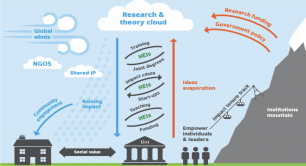

Nurturing a community of practical, innovation-oriented academics can add both prestige and social impact to education institutions. So why aren’t more of them doing so? We speak to some of a new generation of pracademics who emphasise the benefits of looking beyond lecture halls, and share their experience of overcoming the barriers to ‘walking the talk’ of social innovation.

“A pracademic walks the talk. Academic work and on the ground practical experience contribute to progress in social innovation.”

So says Edwin Salonga, a lecturer at Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines and a speaker at the launch this summer of new research on social innovation in higher education in east Asia.

The series of reports, led by the British Council and the University of Northampton, aimed to explore the social innovation ecosystem of five countries: Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Korea and the Philippines. At the online launch of the series, the discussion focused on the tension between theory and practice and the critical role that pracademics can play in cultivating inclusive growth and sustainable communities.

There is a strong desire among academics to engage in social innovation research that has practical relevance for communities. But there are still many barriers to academics engaging in practical research

The term pracademics should be a misnomer. Surely every academic should be interested in and engaged with the broader community? The need to deploy a specific word suggests it’s not so simple.

Walking the talk

“As an academic in social innovation, you should be a social innovator yourself,” Truong Thi Nam Thang (pictured), an associate professor at the Center for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Vietnam’s National Economics University tells Pioneers Post.

“As an academic in social innovation, you should be a social innovator yourself,” Truong Thi Nam Thang (pictured), an associate professor at the Center for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Vietnam’s National Economics University tells Pioneers Post.

Thang is also an ecosystem builder and social enterprise impact investor. Her innovation activity includes creating a digital map of social enterprises in Vietnam, annual social enterprise awards, a coworking space, and a donor network for social innovation academic training.

- Read: Vietnam: The journey to inspire young social enterprise pioneers

- Read: New fuel for the social innovation research locomotive in Hong Kong

So a pracademic combines academic expertise with social innovation practice.

What that combination means day to day, says Salonga, is collaborating with partners outside academia, from local communities to national governments. As a pracademic, Salonga uses his academic training to develop protocols, tools and design interventions to help social innovators and entrepreneurs with their development initiatives. The aim of SEDPI – an organisation focused on microfinance, social entrepreneurship and financial education chaired by Salonga – is to empower disadvantaged people economically and, in turn, help community cohesion.

Ari Margiono (pictured), head of the Centre for Innovation, Design and Entrepreneurship Research at Bina Nusantara University, Indonesia, runs a 'social innovation camp' for master's students at the university's business school, where participants work on solutions to problems such as poverty and marginalisation. The camp has two core objectives – to build empathy among students and support communities to develop sustainable enterprises, he explains.

Ari Margiono (pictured), head of the Centre for Innovation, Design and Entrepreneurship Research at Bina Nusantara University, Indonesia, runs a 'social innovation camp' for master's students at the university's business school, where participants work on solutions to problems such as poverty and marginalisation. The camp has two core objectives – to build empathy among students and support communities to develop sustainable enterprises, he explains.

“Our students learn to spot organisational problems in local social enterprises. But the most meaningful contributions are usually related to strategic support, such as the development of social business models for social enterprises.”

In the UK, practical engagement and social innovation still sit on the margins of academic work. Nevertheless, there are some notable exceptions. One of the UK’s newest universities, the University of Northampton, has been a social impact investor since 2011, devoting money and staff time to help socially inclusive causes. Its partnership with Goodwill Solutions CIC, a local logistics enterprise that trains and hires ex-offenders, was recognised with a Queen’s Award for Enterprise in 2020.

Projects like these can be hugely important and prestigious for universities. So why aren’t they part of an academic's job description?

Academic walls

“There is a strong desire among academics to engage in social innovation research that has practical relevance for communities,” says Richard Hazenberg (pictured), professor of social innovation at Northampton university, and lead researcher in this British Council research project. “But here there are still many barriers to academics engaging in practical research and reaching out.”

“There is a strong desire among academics to engage in social innovation research that has practical relevance for communities,” says Richard Hazenberg (pictured), professor of social innovation at Northampton university, and lead researcher in this British Council research project. “But here there are still many barriers to academics engaging in practical research and reaching out.”

Among those barriers in the UK, as elsewhere, are the relationship between career progression and publishing in highly-ranked academic journals which prefer theoretical over practical research.

And, he says, the policy environment doesn’t help, with politics and therefore policy swinging between “neoliberal or market-based solutions, or state-led public interventions”.

Salonga agrees that the traditional academic career path is a barrier to practical engagement. ‘Pracademia’ is viewed as an optional extra – hardly an incentive for already overworked staff. Rewards are for academic achievement and publication in high-status journals rather than community engagement.

Margiono also cites the same institutional barriers, but says the research revealed that many social innovation academics are entrepreneurial themselves. “They then become the catalyst that breaks down those institutional barriers… Some university leaders buy in to this, and it slowly changes university policy."

That puts a high onus on academics to lead change, which is often tricky given the burdens of their role. Should they have to overperform just to get universities to reach out? Perhaps university leaders should start reflecting on the benefits of socially active academics and change their staff development practices?

I pride myself that, as a lecturer, I am still able to keep my full-time job as a development worker

Salonga’s experience would seem to uphold this view. At his university, pracademics are offered fewer teaching hours and institutional recognition if they embark on research and community engagement work.

“The university seeks out and keeps pracademics. I pride myself that, as a lecturer, I am still able to keep my full-time job as a development worker,” he says, referring to his roles as chair of SEDPI and country programme manager in the Philippines of the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center.

Releasing pracademics from the full-time burden of traditional research and teaching is critical for other reasons too. Thang points out that, while pracademic work offers many benefits, including a better intersection of theory and practice and impact, the drawbacks are the need to multi-skill, and the time and effort required.

The cons can put women academics at a disadvantage. “Being a woman with a family and career and being an influencer is hard, because of the culture of low support to women with high profiles,” she says.

So universities need to think about institutional support for pracademics and the specific issues that affect groups likely to face discrimination. It should have every interest in doing so. A lively community of pracademics offers institutional prestige and social impact.

It also adds to financial sustainability. Encouraging academics to engage in social innovation activity at Northamptonmeans that their research funding streams include not only traditional research council funding but also income from public, private and third sector contracts.

Pandemic transformations

The Covid-19 pandemic has underlined the critical importance of pracademics. There has never been a time in recent memory when the contribution of scientists, epidemiologists and medicine has been so badly needed, even if many governments override their advice.

While social innovation-type activity was already making inroads into the academe – with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framework, the importance of social impact in the Research Excellence Framework, and the Times Higher Education university impact ratings – Hazenberg says the pandemic is driving this trend further.

“There is no doubt that the Covid crisis – and the many long-term adverse effects that this will have on the economy, health and social care and education and training – will mean that applied research that seeks to alleviate some of these consequences will become critical.

“Certainly, in the last six months we have seen a rise in demand from funders for Covid-related research, and we have submitted several funding bids that either focus on Covid’s impact or have elements within them that explore Covid.”

From what these academics say, drawing on the positive contribution that academics can make to their community means rethinking university missions, even if that means working at an operational distance from the demands of government-driven assessment exercises and traditional academic career structures. The rewards, both for society and universities, are potentially huge.

Maybe the role of a pracademic is an idea that has finally found its time.

Header photo: Pracademic Vincent Rapisura, faculty member of Ateneo de Manila University and president of SEDPI, with micro-entrepreneurs in Mindanao, the Philippines