Malaysia: profit proves problematic

The latest research into social enterprise in Malaysia describes some familiar pros and cons for social entrepreneurs. A lack of awareness about social enterprise means making money and doing good makes for uncomfortable conversations.

The British Council’s latest report on The State of Social Enterprise in Malaysia should provoke wry smiles of recognition on the faces of social entrepreneurs the world over.

The report shows much evidence of gender equality and a surge in the numbers of social enterprises launching over the last five years. Yet cashflow is a concern and finding funding can be frustrating.

So far, so familiar. But in South East Asia’s powerhouse country, which has seen consistent growth in GDP in the last 25 years, the notion of profit is proving problematic, compounded by the fact that there is no legal definition of social enterprise.

The report describes that there is sometimes public unease about doing social good and making a profit.

“I have found it hard to even discuss it with people, because the minute I bring up making money, they look at me like I’m being opportunistic and up to no-good,” one social entrepreneur is quoted as saying in the report. Another describes a common perception that doing good should come with a volunteer mindset, with no money being involved.

The minute I bring up making money, they look at me like I’m being opportunistic and up to no-good

Eisya Azman, a programme manager for the British Council in Malaysia, says: “It’s because most Malaysians are not aware about social enterprises, they’re more familiar with the non-profit structure and charities where you don’t monetise or try to sell products to do good.

“Most Malaysians are not familiar with the concept of doing business while doing good.”

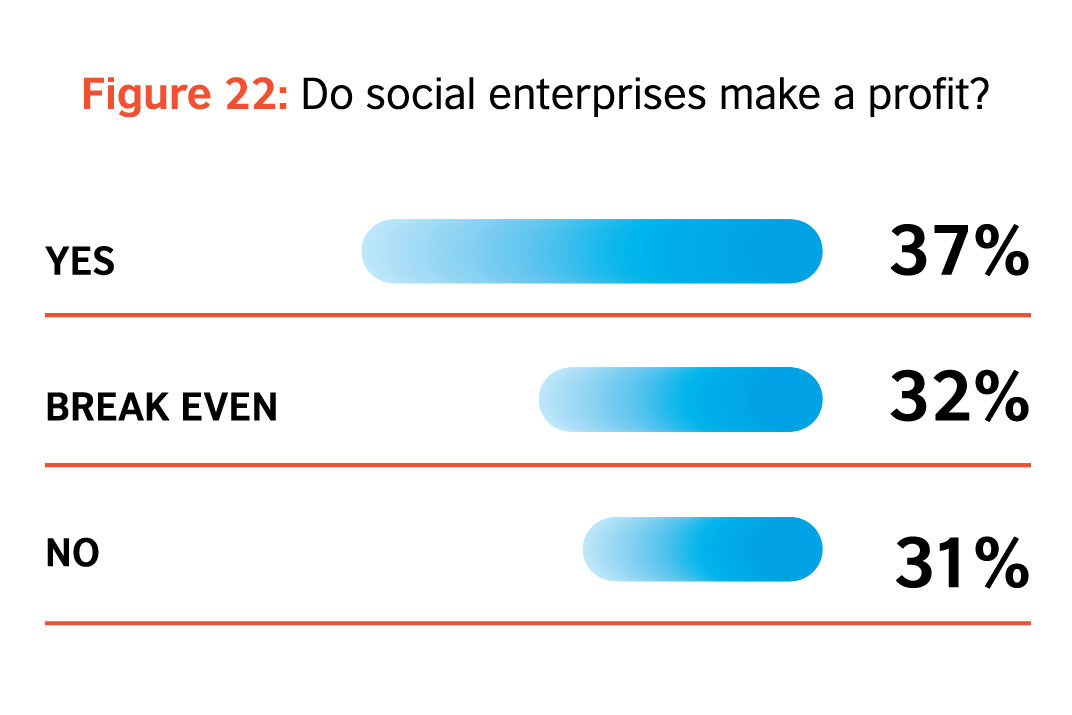

Just more than one-third of the 132 social enterprises surveyed for the report were making a profit, with another third breaking even. The report describes awareness of social enterprise as “not widespread” and social entrepreneurs might not identify themselves as such.

In the introduction to the report, Mohd Redzuan Md Yusof, the minister for entrepreneur development in the country, identifies the lack of recognition of social enterprise as a challenge. He pledges his office will “spearhead the effort to address the challenges that exist within the social entrepreneurship sector” to “create an integrated social entrepreneurship ecosystem.”

This will be seen as further welcome support following the Malaysian Social Enterprise Blueprint, which ran from 2015-2018. This was produced by the Malaysian Global Innovation and Creativity Centre (MaGIC), a government unit tasked with developing the sector.

Where social impact is happening

Creating employment opportunities was the most frequently listed objective by social enterprises in the country. Despite a low national employment rate of 3.42% in 2017, youth unemployment hovers around 10%. Malaysia’s social enterprises are doing their bit, with the report finding that job creation has increased between 2017 and 2018, by 23 per cent for full-time employees and by 33 per cent for part-time staff.

Supporting vulnerable and marginalised communities was the next most popular objective. Beneficiaries include those in rural communities, refugees and disabled people who struggle with limited opportunities for economic independence. Social enterprises strive to upskill these sections of society to improve their chances of earning a living.

Other popular aims were protecting the environment, promoting education and literacy, and improving health and wellbeing.

Nearly all of the social enterprises surveyed said they had plans to grow but listed cashflow as one of their biggest challenges. More than one-third thought the lack of awareness around social enterprise in the country were limiting their chances of growth.

Geography too plays a part in the spread of social enterprise throughout Malaysia. The country consists of two territories that sit 300 miles apart. Western Malaysia occupies the Malay peninsular with Thailand as its northern neighbour and east Malaysia takes up most of the northern part of Borneo island.

The majority of the population (80%) lives in peninsular Malaysia, home to the capital Kuala Lumpur. Two-thirds of social enterprises in the country operate in the capital and the surrounding area of the Klang Valley. This mirrors conventional commerce; the Klang Valley is a key economic region, generating 37% of the country’s GDP.

Five months of research went into the report and the headline figure – the number of social enterprises existing in Malaysia – was hard to come by. Because of the lack of definition, micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), co-operatives and NGOs were all considered.

The figure the British Council arrived at was 20,749 in a country with a population of 32.5 million but given the challenges of definitions, that figure is presented as a rough estimate.

The State of Social Enterprise in Malaysia was published on 12 March by the British Council in partnership with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), the Ministry of Entrepreneur Development Malaysia, and Yayasan Hasanah, a foundation that focuses on Malaysia’s social issues and upscales civil society organisations.

The State of Social Enterprise in Malaysia was published on 12 March by the British Council in partnership with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), the Ministry of Entrepreneur Development Malaysia, and Yayasan Hasanah, a foundation that focuses on Malaysia’s social issues and upscales civil society organisations.

Armida Salsiah Alisjahbana, United Nations under secretary general and executive secretary of UNESCAP, says that social enterprises in Malaysia could help realise the Sustainable Development Goals and pledged further support from the UN.

“United Nations ESCAP is pleased to partner in the publication of this report, to provide an evidence base and support policy development to further strengthen the social enterprise sector,” she says.