Northern Ireland’s social enterprises “floored” by Covid-19 – but it’s not all doom and gloom

Northern Irish social enterprises have already faced more than their fair share of uncertainty and delay – and now Covid-19 threatens to derail a growing movement. Will it pull through?

A Friday evening in January 2017, and Northern Ireland’s advocates of social enterprise were feeling upbeat. A proposed Social Value Act – which would require commissioners of public services to factor in social impact when choosing contractors – had passed another milestone, and would now be brought to the Northern Ireland Assembly. Finally, it could catch up with the rest of the UK, where such legislation had been in place for several years.

Then, a few days later, politics intervened. A dispute between the main parties led to the Assembly being dissolved – and it would be three whole years before a power-sharing government could once more be formed.

But by March of this year a much, much bigger obstacle had emerged.

The Covid-19 pandemic is likely to delay not only the long-awaited social value act, but also – due to government-imposed closures of non-essential businesses since the second half of March – threatens the very existence of social enterprises themselves. Some 27% of those in Northern Ireland say they won’t survive beyond the end of May without help, according to research in late April by membership body Social Enterprise NI. Forty-three percent of those polled feared they wouldn’t last beyond June.

You can qualify for business support if you're an amusement arcade or a gun club or a bingo hall. But you can't qualify if you’re a social enterprise

Government support has helped some: nearly two-thirds of Northern Irish social businesses are considering or have already used the UK’s furlough scheme, which covers 80% of salaries for employees put on temporary leave while business activity is on hold. But Social Enterprise NI argues – as do its counterparts across the UK – that social enterprises are so far getting less than what’s being offered to commercial businesses. Small business grants, for instance, are currently only available to those who pay business rates, which excludes those registered as charities. Some of these may benefit from the Northern Irish allocation of a UK-wide charity bailout of £750m. But more clarity “is badly needed”, says Social Enterprise NI director Colin Jess. Asked if they were eligible for the small business grant, 60% of respondents told Social Enterprise NI that they weren’t – and another 27% did not know.

|

Northern Ireland’s 840 social enterprises...

Source: Social Enterprise NI, 2019 |

Social Enterprise NI’s team of just three staff has spent the past weeks furiously penning letters, presenting to parliamentarians, and tweeting to get its message out. Jess is just as vocal from his personal Twitter account, but speaking to Pioneers Post he appears more optimistic, naming several individuals in government who actively support the movement, and saying it’s understandable that schemes devised so quickly won’t “hit everyone first time round”. He considers the issue more technical, than political: “I do believe there is a will and there is funding set aside – all they’re looking for is how.” He has proposed a workaround that would allow officials to identify those exempt from paying business rates, and is hopeful this would open up grants to many more.

But meanwhile, some still feel it’s a sign that social enterprises aren’t really valued for the positive benefits they provide.

Above: A choir group making use of the spaces provided by Fermanagh House (credit: Fermanagh House)

“You can qualify for business support if you're an amusement arcade or a gun club or a bingo hall. But you can't qualify if you’re a social enterprise providing space for people to convene and those with challenges in their life,” says Lauri McCusker, director at Fermanagh Trust, a community foundation that among others runs Fermanagh House, a purpose-built centre housing local charities and community groups. “It just seems a bit… well, a bit unfair.”

Some suggest it’s because social enterprise doesn’t easily fit within the remit of one government department (such as communities, health or education). Many organisations use hybrid legal structures – structured as both a company and a charity, for instance. “The challenge is where social enterprises sit… there’s no real home for them,” says Maeve Monaghan, CEO of Belfast-based NOW Group, which helps people with learning difficulties and autism into good jobs. Dave Linton, founder of buy-one, give-one bag business Madlug (and also a board member at Social Enterprise NI), believes the sheer diversity of social enterprises can make it hard for people to support the movement.

Trading on faith

Charities and social enterprises have long been encouraged to generate more of their own income by selling goods or services. In a bitter twist of irony, those who took that advice on board now face a steep decline in income, Jess says, while those still dependent on grants have at least been able to turn to sympathetic funders. As he told members of the Assembly in a recent economy committee meeting, “the fact that they’ve been innovative and entrepreneurial has actually gone against them.” Social Enterprise NI itself may not be immune, either: while it gets some funding from the government in return for delivering a programme of work on social enterprise, it also relies on membership fees, as well as corporate sponsorship and conferences. Collecting this year’s membership money may well be challenging.

Charities and social enterprises have long been encouraged to generate more of their own income by selling goods or services. In a bitter twist of irony, those who took that advice on board now face a steep decline in income, Jess says, while those still dependent on grants have at least been able to turn to sympathetic funders. As he told members of the Assembly in a recent economy committee meeting, “the fact that they’ve been innovative and entrepreneurial has actually gone against them.” Social Enterprise NI itself may not be immune, either: while it gets some funding from the government in return for delivering a programme of work on social enterprise, it also relies on membership fees, as well as corporate sponsorship and conferences. Collecting this year’s membership money may well be challenging.

The fact that they’ve been innovative and entrepreneurial has actually gone against them

Even the most robust organisations are reeling from the unpredicted arrival of the coronavirus. NOW Group was founded in 2001 and runs a catering business and four cafés; CEO Monaghan (pictured) was named an exceptional leader in the 2018 WISE100 awards for leading a growing business. But even she and her colleagues “were still floored by this”, she says. The “most shocking thing”, she adds, was realising their forward planning had always focused on reducing reliance on government money, not on cushioning potential blows to its traded income. The company has furloughed about a third of its 120 staff and sustained some revenue by offering catering services to key workers. It has also been able to access the small business grant.

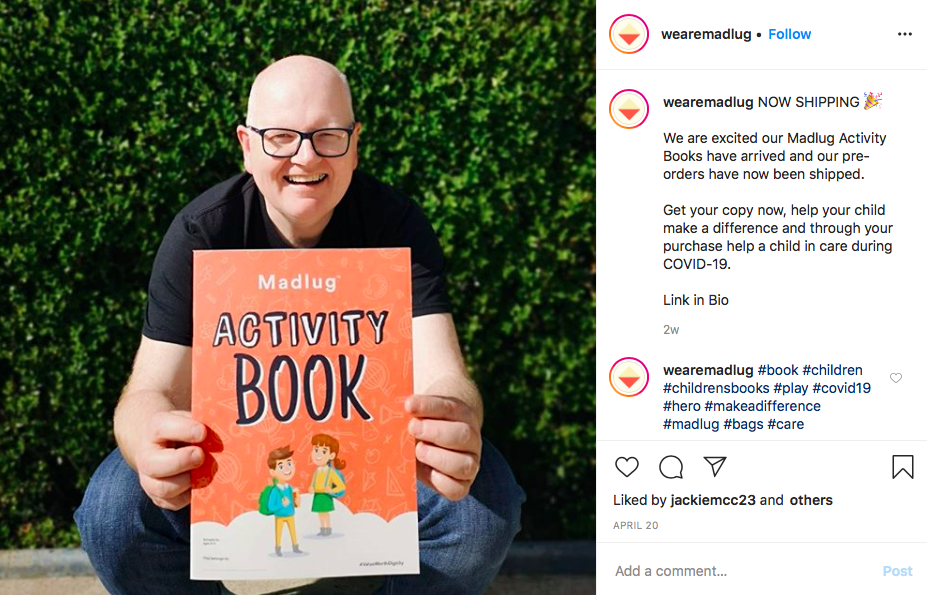

For some, the current upheaval offers opportunities. Madlug, which generates all of its own income through sales of its own-brand bags to consumers and corporate buyers, has seen a huge drop in revenue since the virus hit. But the company has now developed new products that generate revenue while serving its social mission (see box below). The company is also relatively well-cushioned: it employs just three staff – Linton says they’ve been “very cautious” about expansion in the past – and hopes to claim £10,000 from the government small business grant.

Above: Madlug founder Dave Linton presenting the company's new activity book (credit: Madlug/Instagram)

But many other social enterprises can’t be as agile. Fermanagh House has eight meeting rooms for hire and rents office space to around 12 local charities. It is currently helping grassroots groups needing things like photocopiers, has set up a phone befriending scheme and maintains a listing of local delivery and support services. It has furloughed some staff, says McCusker, but the closure of the building means losing an expected £60,000 of income between April and June.

Long-term casualties

For social entrepreneurs, the biggest worries are about cash flow, and that hard-won customers may turn to other suppliers while their own operations are stalled. But the other major concern, according to Social Enterprise NI, is the effect of Covid-19 on the mental health and isolation of service users. (Nearly half of Northern Ireland’s social enterprises focus on improving health and wellbeing.) Jess fears the long-term repercussions: “I think that could be one of the casualties out of this crisis”.

One in seven of NOW Group’s staff have a disability, and it provides 100 training placements a year for people with learning difficulties. There are clearly “sensitivities” when it comes to furloughing someone who’s already vulnerable, says Monaghan: it can be hard for some people to understand what it means. Her company is looking at designing aids to help with this, based on its expertise in creating JAM (‘just a minute’) cards that help people with autism or communication barriers to navigate daily life.

But, longer term, redundancies are likely to follow. Hospitality and catering sectors, for example, employ many of those entering the job market for the first time, and look set to be extremely hard hit by the crisis.

Above: an employee at NOW Group's Loaf Cafe (credit: NOW Group)

The coronavirus may prompt some silver linings. Monaghan says the experience of enforced homeworking could help drive new ways of working in future, which could lead to more ambitious environmental targets. Jess is pushing for Social Enterprise NI to be part of a proposed taskforce that would consider the future of the economy in Northern Ireland. And even current lobbying pressures, he says, have been an opportunity to more firmly convey the message to Assembly members that social enterprises should be considered businesses, just as their commercial counterparts are.

But all that would be little consolation if the sector itself crumbles. In a place where those in power are easily diverted by deep-seated political divisions, not to mention where the added unknowns of Brexit loom on the horizon, businesses owners could do with some certainty right now.

The hour of need

None are more vulnerable right now than startups, and Jess fears for the future generation of social entrepreneurs, wondering if young people who would otherwise be attracted to this way of doing business “will be forced away” if it looks too difficult to survive.

None are more vulnerable right now than startups, and Jess fears for the future generation of social entrepreneurs, wondering if young people who would otherwise be attracted to this way of doing business “will be forced away” if it looks too difficult to survive.

Nineteen year-old Aimée Clint (pictured), founder of educational publisher Books by Stella, echoes this. She doesn’t believe her government intended to leave out social enterprise, she says, but her frustration is evident – not only as a small business owner but also as a Young Ambassador for Social Enterprise NI: “How could I encourage young people into the sector when the government can’t support us in the hour of need?”

How could I encourage young people into the sector when the government can’t support us in the hour of need?

The hour of need may come to an end soon. On 5 May, Northern Ireland’s economy minister promised a £40m hardship fund for microbusinesses that haven’t been able to access other support. It’s expected to help around 8,000 businesses, and small social enterprises and charities are potentially eligible.

Details of that fund, as well as further news on Northern Ireland’s allocations from the UK’s £750m for charities, are expected in the coming days. At Fermanagh House, in the meantime, the focus is on the next phase, with much work to be done to reconfigure a space that sees up to 250 people – some with health issues that make them more vulnerable – passing through each day.

“We’re going to continue to do what we’re doing,” says McCusker. “It’s not all doom and gloom.”

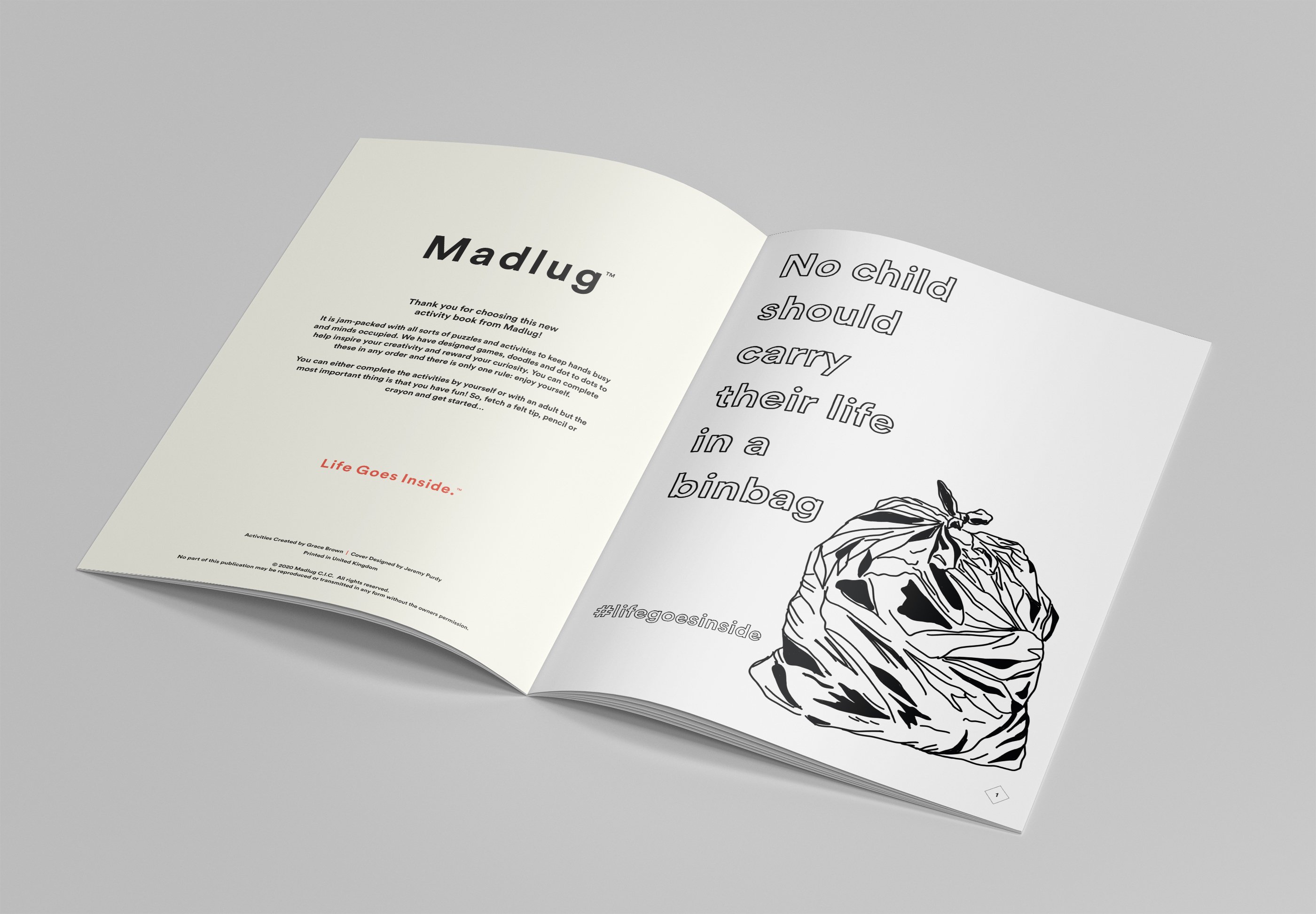

Designs for dignity: MadlugDave Linton says Covid-19 was an opportunity to think creatively. The Belfast-based former youth worker runs Madlug, a social enterprise that gives specially-designed luggage to children in care across the UK, many of whom otherwise resort to moving their belongings from one home to another in a bin bag. Those donations are funded by sales of Madlug’s own-brand backpacks (pictured top), gym bags and accessories to consumers as well as to corporate customers. The company on average shifts 500-600 bags a month. But since the UK went into lockdown in March – in a period that’s typically led by B2B sales – revenue has plummeted. “We could have furloughed staff, applied for grants and stopped things,” says Linton. But he knew that the problem his business aims to address – the fact that kids in the care system too often feel lost and forgotten – wouldn’t stop under Covid-19. In anything, the risks are greater, with social workers currently unable to visit, fostered children unable to see their birth families in person, and care services often stretched.

Keen to maintain momentum, the social enterprise began creating an additional product that would continue to reinforce Madlug’s message – that every child has value, worth and dignity. One of Linton’s two colleagues, an art school graduate, set to work designing an activity book. It’s now being sold to parents looking for something to keep their kids busy under lockdown, and given away to kids in care. The company aims to get the new books sent to up to 3,000 children across the UK. Linton acknowledges his efforts are “scratching the surface” of a large-scale issue: one child enters the UK care system every 15 minutes, and over half are victims of neglect or abuse. But he hopes the books will help to continue driving Madlug’s mission, “and make people aware these kids are unseen”. And despite the huge uncertainty ahead, Linton is still ambitious for the Madlug consumer brand, hoping to see it become a sort of Adidas or Nike “with a social purpose”. That may come down to factors largely out of his control, though – not least whether schools reopen in September and people stock up on new schoolbags. “That’s a big market for us,” he says. |

Header photo: One of Madlug's bags, which are sold to raise money to support children in care (credit: Madlug).