A unique picture of Egypt’s creative businesses – and why experts are hopeful they’ll continue to thrive

Earlier this year researchers published the first ever detailed mapping of Egypt’s creative industries – a first step in understanding the significance of creative businesses to the national economy. These efforts to collect and understand the data across what is a hugely diverse field are even more important post-Covid, as artists, creators and entrepreneurs grapple with the unexpected impact of the pandemic – and policymakers and support organisations look for the best ways to respond. From Cairo, our Young Storymaker Nour Ibrahim reports.

The Covid-19 outbreak is putting the global economy in danger. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has predicted the worst global downturn since the Great Depression and an economic contraction of 1.25% for Africa this year.

While predictions have been made about sectors like food and retail, petroleum, healthcare and tourism, the impact on the creative economy may be more difficult to imagine given the limited data about the sector.

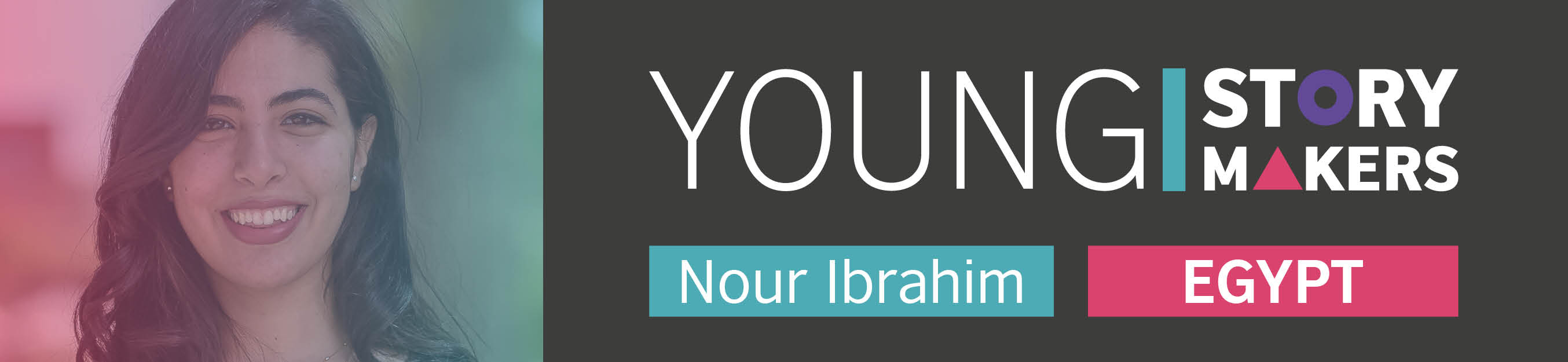

Towards a Creative Economy Framework, a project that recently came to an end, was on a mission to map out Egypt’s creative sectors in a manner that hadn’t been attempted before.

“There may be many initiatives that have tried to make some maps of the creative economy sector but this work was scattered, not structured, so I think this map is a unique one,” Heba Zaki, professor at Cairo University and founder of the university’s business incubator, tells Pioneers Post.

Zaki was involved in the mapping project, which through 2018 and 2019 brought together more than 250 representatives of relevant entities, plus artists, academics and practitioners to map out challenges and opportunities and develop ideas and recommendations for Egypt.

Zaki was involved in the mapping project, which through 2018 and 2019 brought together more than 250 representatives of relevant entities, plus artists, academics and practitioners to map out challenges and opportunities and develop ideas and recommendations for Egypt.

The project was the result of a collaboration between the British Council and the European Union National Institutes of Culture (EUNIC).

“The real value of the project is having most of the institutions working in this sector at the same table and opening the door for in-depth discussions between specialists and individuals with different objectives and missions,” wrote Mohamed Abdel Dayem, director of The Agency for Marketing and Communication, about his participation in the project.

“It is the first step towards understanding the nature, size and degree of participation of the Egyptian creative economy sector in creating jobs, contributing to the Egyptian GDP, and understanding the general or specific challenges of each sub-sector and the cross-cutting challenges between them in order to mark the beginning of a long way to reformulate and build this important sector in Egypt,” he added.

Above: The closing conference of the Towards a Creative Economy Framework project ended on a creative note with a performance of a folk dance by the dancers of Medhat Fawzy Centre for the Stick Arts (credit: Nour Ibrahim)

By bringing together different stakeholders, the project compiled accurate insights that showcase each sector’s actual contribution to the job market, challenges faced by its key players, available resources and the most urgent policy needs. It forms what Zaki describes as a “good foundation” for those who want to explore the sector before and after Covid-19.

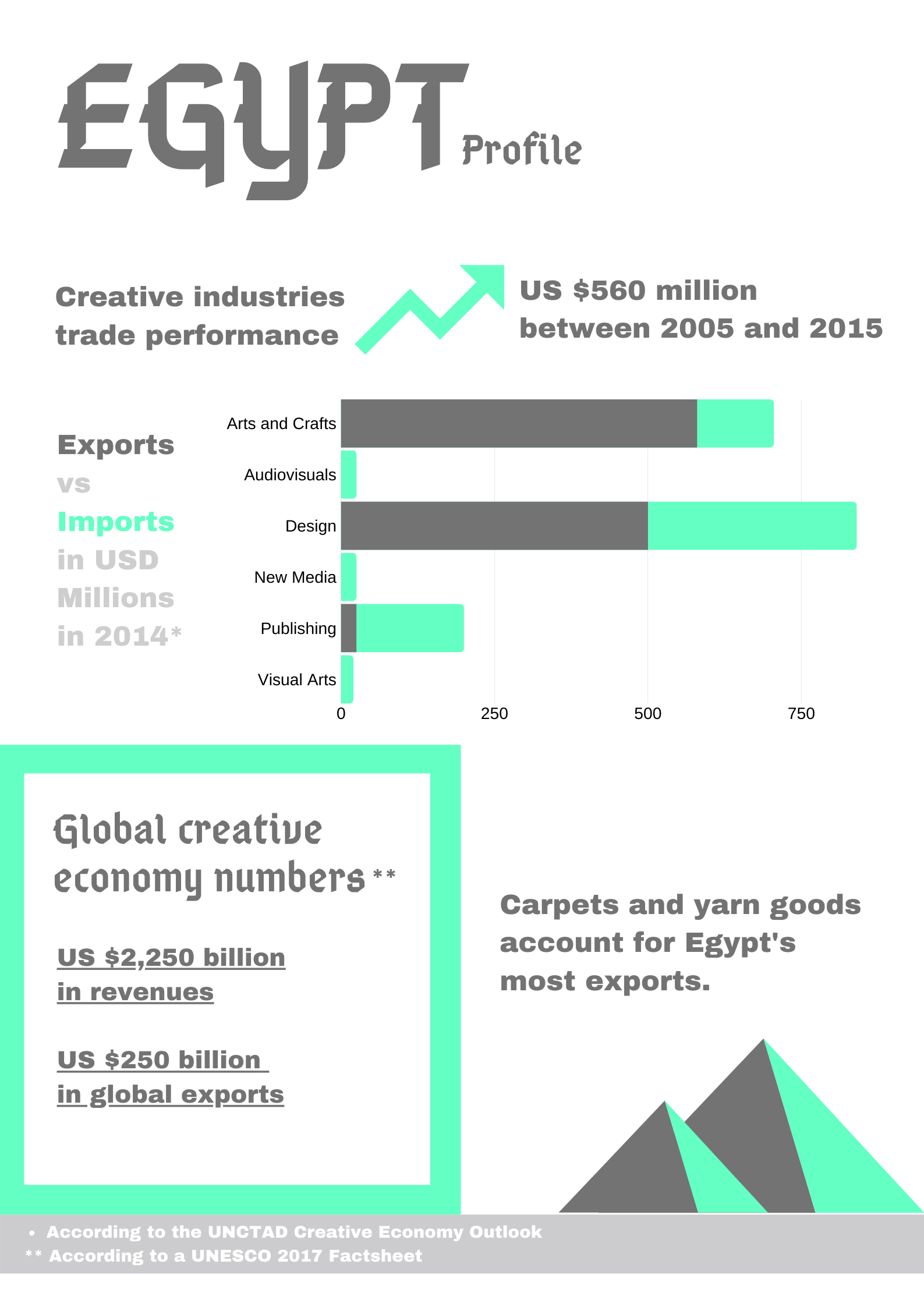

This “foundation” includes a collection of articles written by journalists, practitioners and academics with the aim of defining creative industries and tracing their origins and impacts, a series of occupational maps and summaries of government initiatives and project discussions as well as 12 project proposals across the five covered industries.

Defining an industry

“The ‘creative industries’ is a construct.” This is how consultant and creative economy expert Tom Fleming phrased it at the project’s closing in January, admitting that the different views of what constitutes the sector is challenging for those attempting to examine it.

Fleming designed and supervised the implementation of this project over two years, contributing to the discussions, the mapping and forming of partnerships. Having done some similar work in Egypt 2007, he describes the exercise as “a strategic challenge” because of the need to link many different organisations and agree on goals and outcomes.

That’s not just a challenge in Egypt. The British Council reported that the UK mapped its creative economy for the first time in 1998 and covered 13 sectors at the time, namely advertising, architecture, art and antiques, crafts, design, designer fashion, film, video games, music, performing arts, publishing, software, television and radio.

The creative industries together contribute over £100bn to the UK economy and we have been trying to find similar information for Egypt

That first mapping raised criticism for using a broad definition of the term ‘creative industries’. Described at the time as ‘activities which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property,’ critics argued the loose definition could fit pharmaceuticals and research and development firms, too.

However, as more mappings of the British creative economy were produced, further consensus was reached about the boundaries of the sector and a huge market that was often overlooked came into the spotlight.

“The creative industries together contribute over £100bn to the UK economy and we have been trying through this project to find similar information for Egypt,” said Cathy Costain, head of arts at British Council Egypt, speaking at the project event in January.

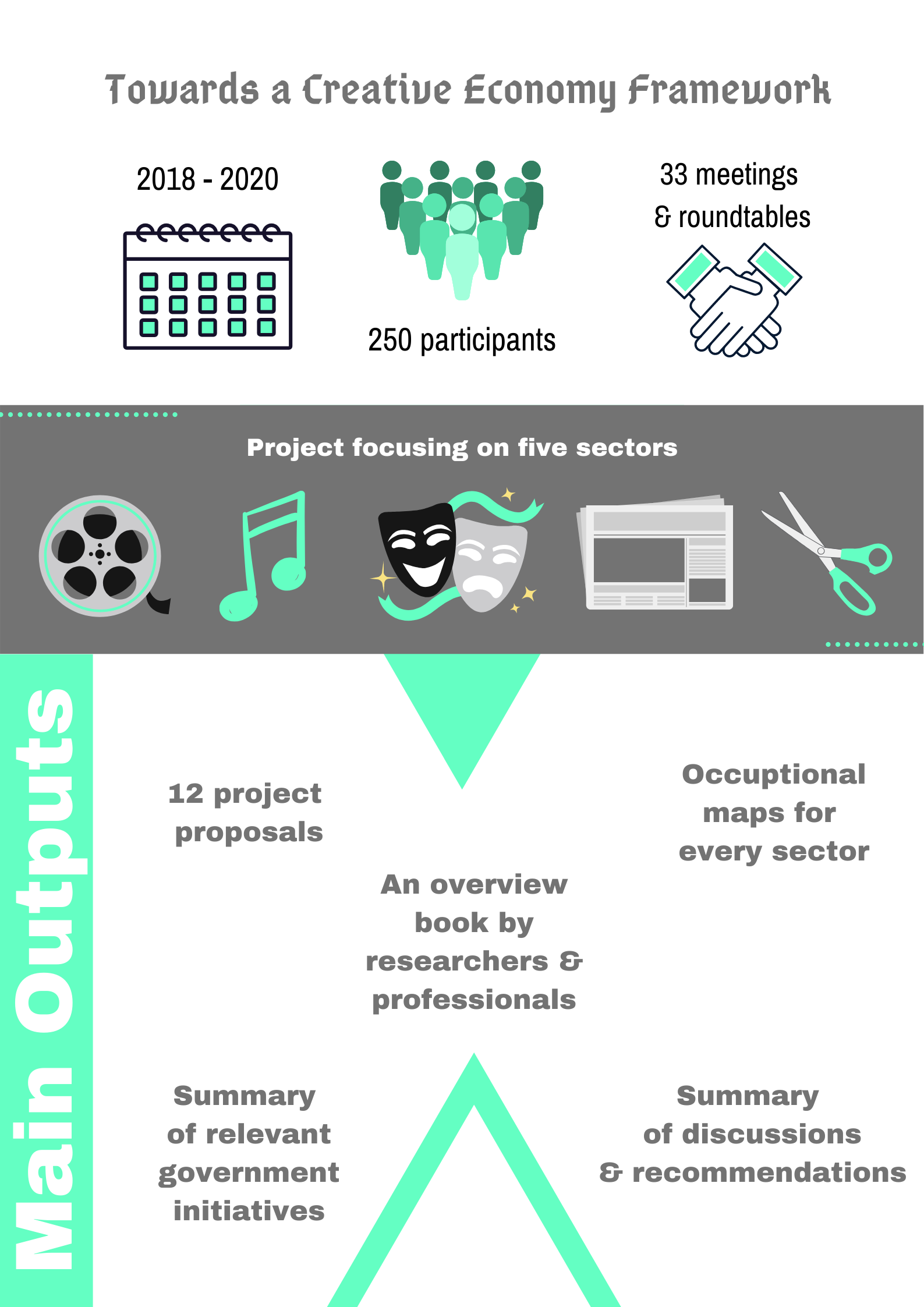

Previous mappings of the Egyptian creative economy have focused on trade, like the Creative Economy Outlook report 2002-2015 produced by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), while other reports compared Egypt to regional neighbours, like the Global Map of Cultural and Creative Industries. The British Council is also preparing to publish a survey of creative and social enterprise in Egypt.

“Creativity is about resourcefulness, innovation, expression and finding ways to survive and thrive,” Fleming said. He added that the creative economy as defined throughout this project was about the extraction of economic value from creativity and heritage.

With this definition in mind, Towards a Creative Economy Framework focused on five creative industries: film, music, performing arts, publishing and design (specifically handicrafts).

“When I travel abroad, I can’t say how many novels were produced in Egypt in a year even though such data could be easily obtained,” said Sherif Bakr, managing director of the publishing house and book distributor Dar Al Arabi. Efforts to both compile numbers and make them available to players in every industry are needed, he added.

Another participant, Usama Ghazali, an entrepreneur and Ashoka fellow, said he had been on a mission to map out the Egyptian handicrafts sector for years. Or, as he put it: “creating an atlas for crafts.”

In the Red Sea territory, I discovered 27 crafts. Out of these, we have completely lost nine

“It started with my interest in national cuisine, that was my entry point. [Cuisine] is a part of creative industries and a way that the society uses to express itself,” Ghazali said.

Alongside starting Yadaweya, an online fair trade store for Egyptian handicrafts, in 2012, Ghazali has been researching and mapping crafts across Egypt’s territories.

“In the Red Sea territory, I discovered 27 crafts. Out of these, we have completely lost nine crafts!”, he said – highlighting the importance of identifying traditional crafts and professions before they become extinct.

|

|

Supporting startups post-Covid

The creative economy is also often linked with entrepreneurship. According to Zaki, who leads the country’s first public university incubator, 8% of all startups globally are in the creative industries.

“Creative industries have two values: economic and cultural values, and that is what we want to encourage,” she said.

At the project’s closing conference, Zaki announced that startups in the creative industries face challenges like lack of skilled labour and high staff turnover, costly prototyping and modelling and lack of professional education. A few months and a pandemic later, she shares some further observations with Pioneers Post.

“[Startups] are now facing challenges concerning finance, operations, the partnerships they were planning to do, the investors who flew away,” she says. “So they face a lot of challenges which is really putting their sector at risk.”

Zaki also believes creative economy startups have suffered even more as the pandemic has affected their supply chains, access to plants and raw materials, and the ability to recruit skilled labour – eventually bringing to a halt their operations and product development.

Recently more people have had time to develop creative hobbies and talents

But this new chapter initiated by the pandemic might also pave the way for a better future for creative businesses by bringing in fresh blood and enhancing the performance of existing startups.

“A lot of people who have lost their jobs wished to establish a startup before the pandemic, but they were really busy and so immersed in their duties and day-to-day work,” says Zaki. More recently, they may have had time to develop creative hobbies and talents.

“There is potential that innovation [prompted by the challenges of Covid-19] will have a great impact on developing this sector because we can rely more on local material rather than the imported material [and] focus more on developing the skills of the workers who work in the workshops of these startups,” she added. Businesses will also have more time to invest in design and to customize products to better fit the local taste.

According to Fleming, identifying a unique, locally-inspired identity is one way to ensure creative economies and businesses thrive. At the conference, he reminded practitioners to ask themselves: “What is distinctive? What are the values that are unique to Egypt that you can develop, nurture and sell?”

Both Zaki and Fleming also highlighted an existing structural imbalance that allows larger companies to significantly drive the economy, accordingly influencing the entire narrative when it comes to funding, policymaking, development and training. However, in our interview with Zaki after the outbreak of Covid-19, she brought a hopeful view.

Smaller companies have the flexibility and the ability to re-innovate their business model quickly and easily

“The power of the big companies still exists of course and it would not fade out in three months,” she says. But some small businesses and startups may have won an advantage during the pandemic: “They have the flexibility and the ability to re-innovate their business model quickly and easily compared to the big companies. So, the imbalance still exists but there is a lot of potential to fill in the gap or to try to rebalance the power.

For many creative businesses, though, challenges continue, with all large gatherings halted since mid-March, leading to the cancellation of thousands of events, shows, concerts, conferences, workshops and exhibitions.

But, with restrictions on shopping venues and the enforcement of curfew, craftsmen may have begun to explore digital outlets to promote and sell their products.

And with 2021 designated International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development, will service and product providers succeed in finding ‘creative’ ways around the current crisis? Zaki is optimistic at least for some businesses: “The best survivors could be the startups who are agile enough and who have innovative tools and skills to innovate their business models and are likely to work with new tools rather than relying on the old ones they used before the pandemic so agility is the key to surviving.”

Nour Ibrahim is a DICE Young Storymaker – one of 14 young journalists recruited by Pioneers Post and the British Council from six countries to report on social and creative enterprise. Photos and infographics by Nour Ibrahim