Are 'ableist' economies depriving themselves of the purple pound?

In rural Indonesia there is a fast-growing group of disabled entrepreneurs taking control of the economic space. Supported by British social consultancy firm Red Ochre, they are training up, honing their business models and spreading skills outwards so that others in their community who face economic exclusion can work for themselves. They signify what countries are missing when they fail to access their ‘purple pound’ – reports DICE Young Storymaker Mathilda Mallinson.

Robert Foster of Red Ochre first met Jimmy Febriyadi in 2015 while delivering social enterprise workshops in Indonesia. Two years later, Febriyadi established the Disability Empowerment Centre (DEC) in Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta. What started as a group of 30 people grew to become today’s 294-strong network of individuals and families with disabilities fighting for socioeconomic independence.

Red Ochre and DEC promised a perfect partnership for the British Council’s DICE (Developing Inclusive Creative Economies) programme, a support programme for transnational partnerships working to improve their respective economies – creatively, socially and financially. So Foster and Febriyadi teamed up to create Economic Empowerment for Entrepreneurs with Disability (EEED).

“There’s enormous potential in the Indonesian social enterprise space,” says Foster. “In the UK, we see the most populous Muslim state and an emerging economy, but if we look deeper there are vast areas of opportunity, from protecting cultural intangibles to reducing waste and pollution in local manufacture.”

DEC entrepreneurs do just that, commercialising unique local crafts to develop culture-rich products, often from recycled materials.

Halfway into a year-long training programme curated by Red Ochre, they are evolving their social enterprises through new marketing and management techniques.

Febriyadi worries economic growth could threaten social priorities, and sees partnership as the antidote. “Red Ochre has much experience in this matter: how to run a business but not forget the social side.”

Skills form only part of the training, says Foster. “A social entrepreneur also has to believe in what they want to achieve. Poverty goes beyond lack of resources – it includes aspirational poverty. Some DEC members have a very limited view of what success could look like for them. We are doing our best to provide a safe space where beneficiaries can develop a meaningful vision of the future; to find their voice and self.”

In May 2019, a group of entrepreneurs were flown from Indonesia to the UK to receive the initial two-week training session in London (the rest of the training occurs in Indonesia). Of course, the learning is not one-way. “London-based social enterprises that met the Indonesian delegation were inspired by their ambition and positive attitude,” said Foster.

For EEED, positivity is the prize. The programme is designed to create not just entrepreneurs but champions of change. The whole idea of the training is 'prolificacy': turning students into teachers.

The programme is designed to create not just entrepreneurs but champions of change.

“We are trying to become more accepted by the surrounding community by increasing self-confidence and spreading this confidence,” says Febriyadi. “By being examples to others that they too can be empowered.”

Why is change needed?

Indonesia has made recent moves towards improving disability rights. In 2011, the government ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; in 2016, it legislated for equal treatment of all people regardless of disability; and in 2017, 14 city mayors signed a charter to make the archipelago’s urban centres accessible for all.

But activists say progress trails behind in practice. Stigma around disability and mental illness forces people into seclusion. In October 2018, Human Rights Watch published a report estimating that over 12,800 Indonesians with psychosocial disabilities were being shackled inside their homes by family members trying to conceal them from society.

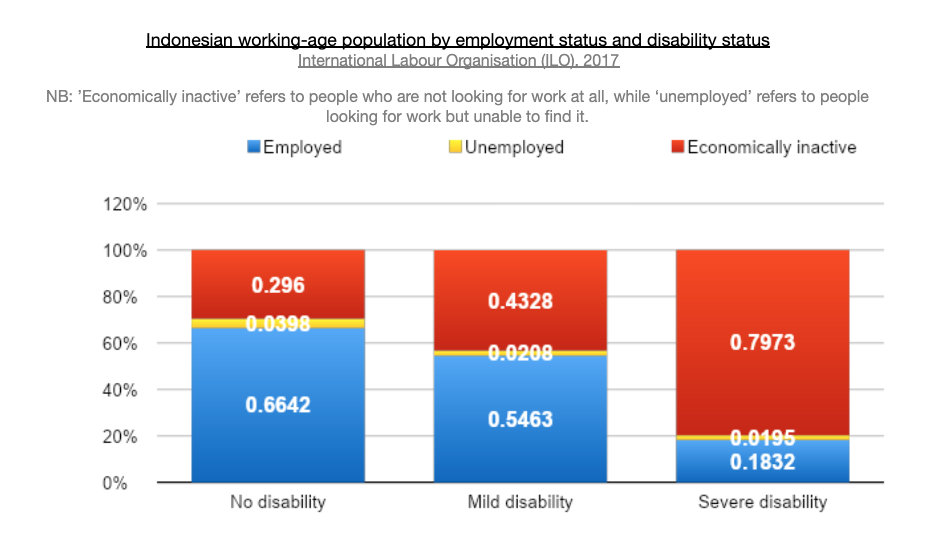

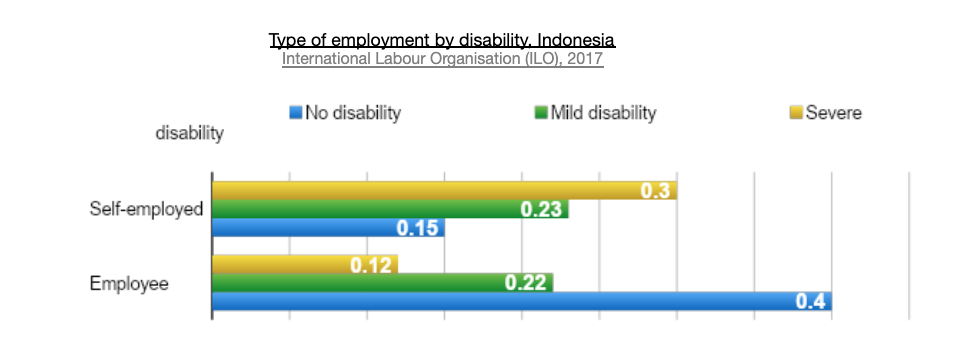

The workforce reflects this invisibility.

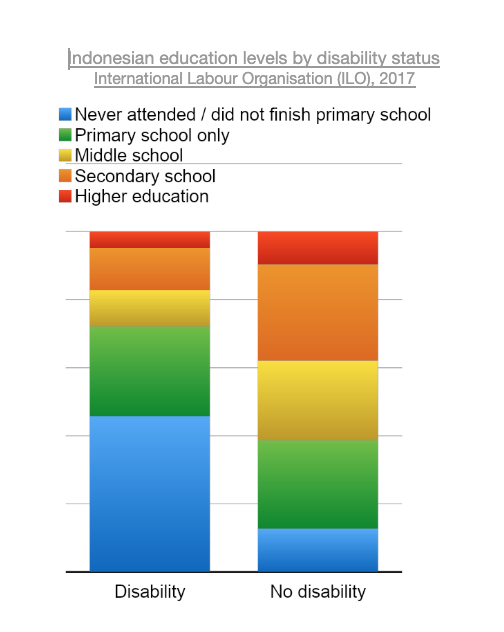

Some of this disparity can be traced to education, with disabled children often being excluded from schooling due to discrimination, a lack of trained teachers and assistive devices, inaccessible facilities, long distances to school, poor sanitation facilities, and so on.

Some of this disparity can be traced to education, with disabled children often being excluded from schooling due to discrimination, a lack of trained teachers and assistive devices, inaccessible facilities, long distances to school, poor sanitation facilities, and so on.

As Foster found during Red Ochre’s London training session, educational exclusion risks pushing out highly competent workers. Trainees’ education levels ranged from tertiary to primary but “the wide gap wasn’t overly noticeable during sessions, which I think is testimony to the willingness of participants to engage and learn”.

As Foster found during Red Ochre’s London training session, educational exclusion risks pushing out highly competent workers. Trainees’ education levels ranged from tertiary to primary but “the wide gap wasn’t overly noticeable during sessions, which I think is testimony to the willingness of participants to engage and learn”.

While income opportunities are reduced for people with disabilities, they often have additional living costs (medical, comfort, hygiene) – this creates a poverty trap. Parents of disabled children have to stay home to meet extra care requirements, while simultaneously working to afford extra needs. Febriyadi says managing household expenditure becomes too much for some. “Gunung Kidul has high suicide rates often caused by debts and loan sharks.”

EEED training incorporates family finances to help tackle this problem.

Puji Lester is one of EEED’s trainee entrepreneurs. His business produces hand-made woven mats out of recycled fabrics. He has children with disabilities, and says balancing work and care is the biggest daily struggle. It was precisely this struggle, however, that led to business innovation.

“We thought about how to meet the children’s financial needs without leaving them alone while we worked. That’s when I noticed leftover cloths, flannels and patches piling up unused. I learned to turn them into woven mats by watching YouTube, and taught other friends to do the same.”

I noticed leftover cloths, flannels and patches piling up unused. I learned to turn them into woven mats by watching YouTube and taught friends to do the same.

A global issue

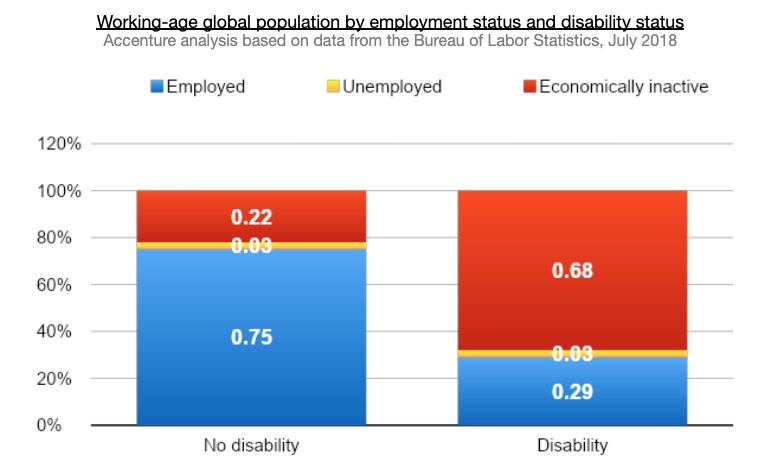

Around the world there is a population the size of China living with disabilities. One thing that unites them all is the disproportionate difficulty they face finding employment, due to various social barriers.

In this sense, EEED’s UK and Indonesian partners operate in similar contexts.

“Initially I thought that the UK had fundamentally sorted the issues with accessibility. Walking with disabled people, at least metaphorically, during their time with us in London showed me my thinking was flawed. Quotas for disabled people in the workplace are enshrined in the Indonesian constitution, which is more than the UK has,” said Foster.

Quotas for disabled people in the workplace are enshrined in the Indonesian constitution, which is more than the UK has.

In November 2016, a UN inquiry condemned the UK for “systematic violations of the rights of disabled people”, tying this issue largely to austerity.

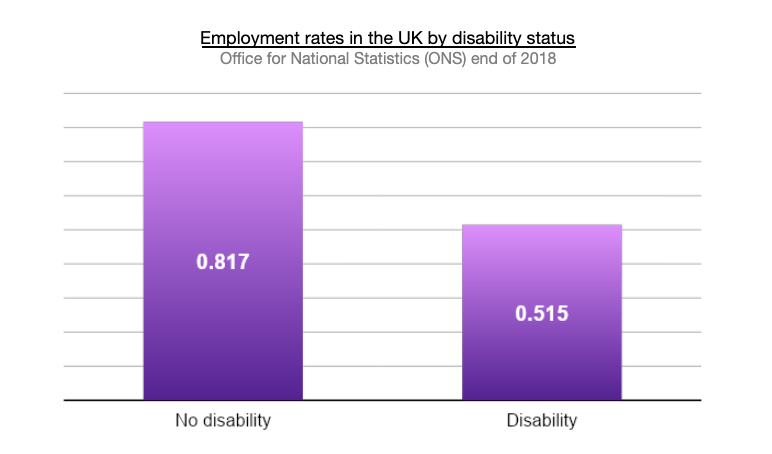

“The inclusion of disabled people in the UK employment space is shocking,” says Allan Hennessy, a British lawyer and Havard scholar of equality law, who is himself disabled.

“The inclusion of disabled people in the UK employment space is shocking,” says Allan Hennessy, a British lawyer and Havard scholar of equality law, who is himself disabled.

“The approach that British society has taken to us has been one of welfare rather than access to the market. It’s because of this patronising stance that the workspace has by and large been shut off to disabled people.”

According to Hennessy, accessibility schemes in the UK are seen as “helping hands to people who are really just liabilities”, rather than fundamental acknowledgment of disabled people’s abilities. This makes them largely unhelpful.

For example, the 2010 Equality Act prohibits direct and indirect discrimination by employers, requiring them to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to accommodate disabled employees (e.g. providing auxiliary aids or ergonomic chairs). But there is a loophole: employers can justify indirect discrimination – the decision not to hire someone because of their disability – if they can prove it to be an ‘occupational requirement’. Hennessy believes this justification is overused.

“It is very easy for employers to plead this defence. They have to convince a (probably able-bodied) judge that taking on a disabled employee would be a nightmare for them; they benefit from the unconscious bias of judges. If, instead, society actually acknowledged the capabilities of disabled people, employers would simply make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to accomodate them, as stipulated in the Equality Act.”

The UK government has pledged to get one million more disabled people into employment by 2027, which would mark a growth of 29% on current levels. But a National Audit Office (NAO) report on the Department for Work and Pensions found “it does not understand enough to frame a full implementation strategy for helping more disabled people to work”.

“Given the Department has had programmes in place to support disabled people for over half a century, it is disappointing that it is not further ahead in knowing what works,” the report concludes.

Costs to society

The economic cost of excluding women and men with disabilities is 3%-7% of a country’s GDP, according to estimates by the International Labour Organisation. This wealth source is called the ‘purple pound’.

Disproportionately, when it does appear, it is made through self-employment and tough entrepreneurialism. Jane Hunt, an adviser with the Disabled Entrepreneurs’ Network (DEN), says clients often opt for self-employment due to their struggles to be included in mainstream employment.

They still face many barriers going alone, as information and training opportunities are not made widely accessible.

EEED is one movement of mutual support that is working to shatter these barriers.

As societies make glacial progress towards inclusivity, overlooked talents are taking control and clearing their own space in the market.

Mathilda Mallinson is a DICE Young Storymaker – one of fourteen young journalists recruited by Pioneers Post and the British Council from six countries to report on social and creative enterprise around the world.