Play for the planet: The favela youth redesigning gaming from Brazil’s north-east

How do you make the tech start-up scene more inclusive? This is the challenge that UK-based social enterprise, Signifier, and Brazil’s leading IT science park, Porto Digital, have teamed up to address. Our DICE Young Storymaker Yael Berman reports from Recife on the video games developed by a new generation of designers and developers – whose creations educate players on environmental issues while challenging stereotypes and drawing instead from (an often overlooked) rich cultural heritage.

The favelas of Pilar, Brasília Teimosa and Pina are a mere five kilometres from the area of restored colonial buildings and museums where Porto Digital, Brazil’s ‘Silicon Valley’ in the city of Recife, is based – but they might as well be a world away. These favelas (as slum areas are called) are full of young people who might have joined the IT hub’s workforce but have not, at least until now.

A partnership between Porto Digital and UK-based consultancy and think tank Signifier, whose work supports diversity inside cultural and creative organisations, is working to change this reality. Supported by the British Council’s Developing Inclusive and Creative Economies (DICE) programme, they created the project Ressignifica (in English, ‘Re-Signifier’), which aims to train and include people from more diverse backgrounds than the “mainly white, middle class people” who make up the bulk of Porto Digital’s workforce, according to Professor Marcos Primo, Ressignifica’s head in Recife.

Above: a Ressignifica workshop. Ressignifica aims to train and include people from more diverse backgrounds than the mainly white, middle class people who currently make up the bulk of Porto Digital’s workforce.

One of those taking part in this new initiative is Danielle Brandão, 23. She lives in the favela of Pina, which borders rich areas of the city, and together with her teammates, was selected to take part in the acceleration part of the project, called ‘Mind The Bizz’. The training focuses on things like business planning, finance and creativity. “The idea is to turn prototypes into companies, and transform something that could be a hobby for the young participants into an entrepreneurial career,” explains Primo. Twelve groups are taking part, with approximately 40 young people in total – of which 45% are women and 88% are black.

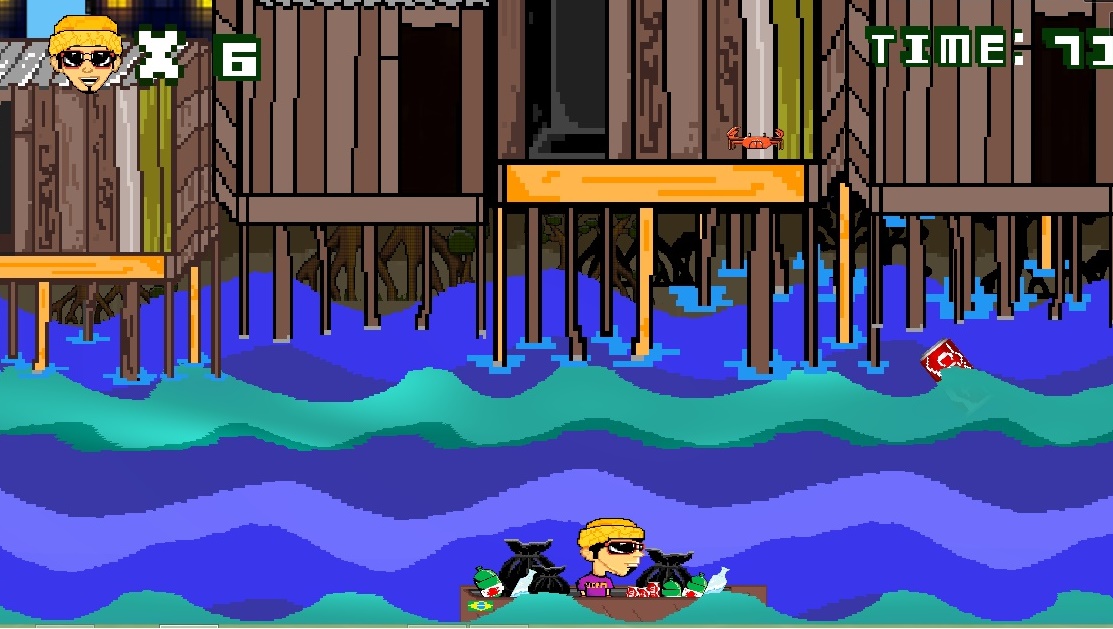

Brandão’s group is developing a video game called ‘Mangue&Beach’. The name is a play on words that references an important cultural movement known as Manguebeat, which started shaking Recife’s music scene in the 1990s. Named for the mangroves (mangues in Portuguese) on which the city was built, Manguebeat has been defined as a “mixture of hip-hop and Maracatu beats” – dance and rhythm based on percussion created by afro-Brazilians in the state of Pernambuco as a form of cultural resistance during the Portuguese colonial period in Brazil. However, its founders say it is more about a cultural scene “as rich and diverse as the mangroves,” according to Renato L, a journalist who helped found the movement.

Watch Chico Science and Nação Zumbi’s music video, Maracatu Atômico, on YouTube.

The main character of the Mangue&Beach video game is Chico Grove, a name inspired by Chico Science, an icon in Brazil’s music scene and one of Manguebeat’s founders. The character’s mission is to clean the mangrove and the beach by collecting and recycling trash. The game’s soundtrack is pure Manguebeat, and the design includes symbols of that scene such as crabs and vultures. The whole layout takes you back to the 90s.

Above: a still from the Mangue&Beach game, showing the main character Chico Grove in action.

The six young developers in Brandão’s group, who all come from favelas that are located near Porto Digital, say the video game is inspired by the music as well as by their life experience. “If I wasn’t born in this favela [Pina], I would not see the world the way I do. And I wouldn´t want to change the world the way I do,” says Brandão. This also explains the relation between the game and the Manguebeat movement, which was always concerned with social issues affecting Brazil and Recife. “We faced high levels of inequality, rampant real estate speculation and many social problems,” explains Renato L. “And the city was culturally stagnant. It was a strong feeling at the time. There was kind of an energy stopped by a dam, that Manguebeat helped open.”

By breaching this dam, Mangue&Beach’s creators are simultaneously addressing social and environmental issues and celebrating the culture of Brazil’s north-east. “We wanted to stay away from the stereotypes usually related to the north-east of the country, of poverty and drought,” says Brandão. And, she adds: “We wanted to create an educational game, which made people aware of the importance of cleaning the mangroves, the rivers and the beach. Pollution is not only bad for the environment, it affects the fishermen who rely on fishing for their livelihood”.

Above: Young people and kids having fun in the fishing area of Pina favela (photo credit: Arthur Souza).

The Little Prince in Pernambuco’s regional culture

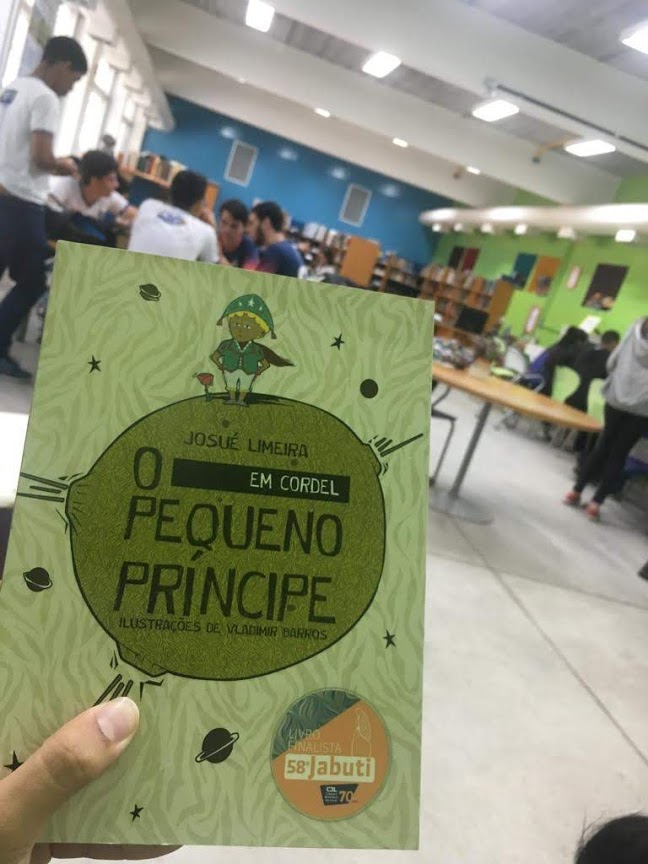

Mangue&Beach is not the only game being developed by young people enrolled in Ressignifica. A group of Recife high school students is working on a game inspired by an adaptation of the book The Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The Pernambuco-based version of the book (pictured) was written by Josué Limeira and illustrated by Vladimir Barros, adapted in the style of Cordel literature, a distinctive genre that became a symbol for north-eastern culture and identity in Brazil. It is composed of verses with rhymes and it is usually illustrated with woodcut art.

The name of the video game is O Pequeno Cabra da Peste, which mashes up the book’s original name with regional slang. ‘Cabra da Peste’ is a popular expression in the north-east of Brazil which is used to refer to someone who is brave and fearless. The main character is the Little Prince – but one who wears the traditional clothes and hat worn by residents of the semi-arid scrubland in the north-east of Brazil. The player’s mission is to collect baobab seeds, clean volcanoes and draw water from wells to keep flowers alive. The Little Prince from the scrubland needs to accomplish those missions while passing through cacti, thorny plants and goats, without getting hurt.

The name of the video game is O Pequeno Cabra da Peste, which mashes up the book’s original name with regional slang. ‘Cabra da Peste’ is a popular expression in the north-east of Brazil which is used to refer to someone who is brave and fearless. The main character is the Little Prince – but one who wears the traditional clothes and hat worn by residents of the semi-arid scrubland in the north-east of Brazil. The player’s mission is to collect baobab seeds, clean volcanoes and draw water from wells to keep flowers alive. The Little Prince from the scrubland needs to accomplish those missions while passing through cacti, thorny plants and goats, without getting hurt.

“The idea is to follow the book’s narrative, so that readers can have one more immersive experience,” explains Vinnicius Rodrigo, 17, one of the developers of the game. He highlights that after each challenge, the game plays regional music based on cordel verses that were written by his group. “We want to promote a full experience inside Pernambuco’s regional culture, that’s why we offer this musical interaction. The idea of the game is to reaffirm the north-east’s cultural identity, showing who we are and what we’ve got,” he says.

Above: A still from the video game O Pequeno Cabra da Peste, inspired by a regional adaptation of The Little Prince.

Changing reality

When creating O Pequeno Cabra da Peste, Rodrigo and his peers thought about the UN Sustainable Development Goals. They are working on Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, especially on target 11.4, which aims to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage”.

The young developers of O Pequeno Cabra da Peste and Mangue&Beach are mindful of the power they have to make the world a better place for future generations, and of the power that comes from the Brazilian north-east and from the favelas. They are tired of the stereotypes of marginalisation and poverty.

“Everybody from our team loves playing video games,” says Brandão. And they’re not alone: according to research by Newzoo, a company focused on games market insights and analytics, Brazil had 76 million players in 2018, making it the 13th largest games market in the world.

“But when we search for Brazilian north-east video games on the internet, it usually focuses on drought and poverty, and when it talks about regional culture, it’s in a superficial way,” says Brandão. She continues: “We know Brazil’s north-east, because we are from here and we live here. Our aim is to show what the north-east is really like, so that people feel represented in video games. We are not feeling represented and we want to change this reality and show it to the world.”

Yael Berman is a DICE Young Storymaker – one of 14 young journalists recruited by Pioneers Post and the British Council from six countries to report on social and creative enterprise.

Header photo: Young people in the fishing area of Pina favela (credit: Arthur Souza)